“Well, an old stump is good for sitting and resting” – and perhaps also for playing

Orna Ben-Zioni & Beeri Ben-Shalom, BO -Landscape Architects

Pippi’s garden was really lovely. You couldn’t say it was well kept, but there were wonderful grass plots that were never cut, and old rosebushes that were full of white and yellow and pink roses–perhaps not such fine roses, but oh, how sweet they smelled! A good many fruit trees grew there too, and, best of all, several ancient oaks and elms that were excellent for climbing.

The trees in Tommy’s and Annika’s garden were not very good for climbing, and besides, their mother was always so afraid they would fall and get hurt that they had never climbed much. But now Pippi said, “Suppose we climb up in the big oak tree?”

Tommy jumped down from the gate at once, delighted with the suggestion. Annika was a little hesitant, but when she saw that the trunk had nubbly places to climb on, she too thought it would be fun to try.

–Pippi Longstocking, by Astrid Lindgren (1945)

Nowadays, children are hardly ever lucky enough to climb trees.

Today’s parents compete with each other as to who will be the most protective of their children. Over recent years, anxiety has become the most desirable quality for the “good parent.” The message is: the more we prevent our kids from engaging in activities that might injure them, the healthier a generation we are raising, one which is safeguarded, protected and overly supervised.

“At the heart of the obsession with safety,” argues Hannah Rosen in her article “Overprotected Children” (published online in the e-journal Alachson, 2014), “is the basic assumption that children are just too fragile, and lack the knowledge required to assess risks in each situation.” Rosen’s article reviews the development of overprotection of children over the past 30 years. It reached a point of having lawsuits filed by parents, for example, due to their child bumping into a log and stumbling in a grove of trees in a play area. She presents a survey of playgrounds that in the 1990s became sterile and boring – safer, yes, but much less interesting.

Rosen describes research studies showing that challenging play environments force children to do what frightens them, to overcome their fears and make decisions. This is a decisive part of the process of maturing and developing. Children who fail to undergo this process suffer from phobias and do not develop the self-confidence necessary for being independent of their parents.

As landscape architects, much of our work involves designing for children. We have recently been partners in the planning of kindergarten and elementary school grounds. We were surprised to be faced with the full force of the phenomenon. Parents demanded that we remove all of the low logs we planned for the grounds we designed, logs which formed the borders of the garden rows in the small garden plots in the schoolyards we designed. The logs, elements for play and practice in balancing, were the focus of parents’ fears that their children would fall and hurt themselves. Once we received a report from the Ministry of Education stating that the school grounds must be free of any protrusions or elements to climb on or bump into. This forced us to close down the little theatre we had planned for the yard – “The children might fall from a height from the seating walls.”

But the legislation and anxiety do not stop at the school or kindergarten fence; they send their feelers into the open spaces, as well, into the places where children have a bigger degree of freedom, places which facilitate free play, experimentation and discovery.

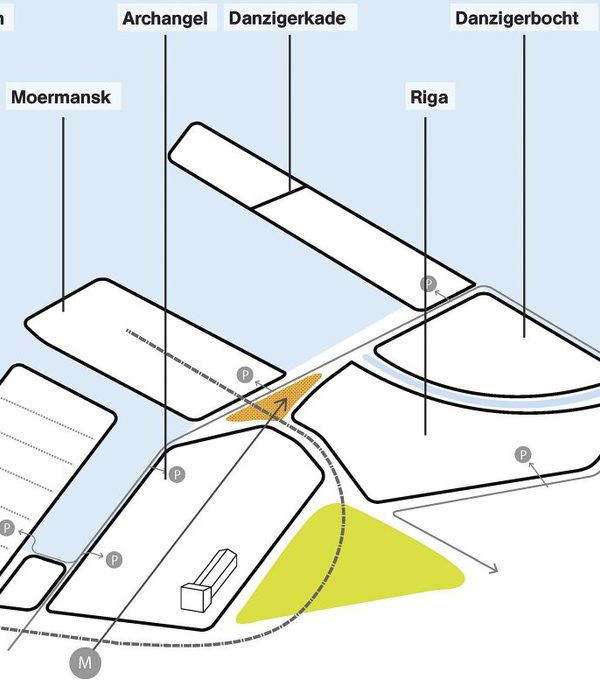

Our office recently received the commission to design Hashomrim Park in Kiryat Tivon, Israel. This is a long-standing playground in the heart of an oak and pine forest which had been stripped of its play installations after failure to comply with the Standards Institute of Israel’s standards. The design concept was to make maximum use of the frame of old trees in the park and use their broad shade. We would lead people towards the play area with paths between the trees while maintaining all of the required safety margins around the playground installations. This is why we made the pathways twist around between, near, and around the trees, taking utmost care to preserve each and every tree which altogether provided immediate quality of the space and a wide shady area.

To our intense regret, the more agencies came to inspect the park, the more they demanded that we cut down more and more trees. At first, it was a recently planted tree, then it was an old tree whose fate was sealed, followed by the order of execution against the trees that were “too close” to the play area. Finally, an order was issued to cut down the tall tree that was growing “too close” to the seating area. Thus, we had to cut down many mature, old trees. We were upset but nevertheless decided that “an old stump is good for sitting and resting (The Giving Tree, Shel Silverstein (1964)) – and perhaps even for playing. We asked the contractor to slice up the tree trunks that had been cut down, and created a sculptural play environment, which (of course) preserved the trees in their original environment, in a slightly different function…

Needless to say, when the trees were cut down, we lost not only the shade required for a playground but the spirit of the park was damaged as well as the essential feeling around which the park was built – and thus we felt that the branch we were sitting on was cut down under us.

There has always been tension between our children’s safety and their development of sense of danger and exposure to challenges supporting growth and maturation. We must make wise decisions, which may sometimes mean that we must understand that “it’s impossible to create the perfect environment for our children, in the same way, that it’s impossible to create perfect children” as Rosen stated. It is worthwhile taking the risk because avoiding risk also has its price.

Landscape architecture: Landscape Arch. Orna Ben-Zioni and Landscape Arch. Beeri Ben-Shalom are partners/owners of BO- Landscape Architects.

Design associate: Landscape Arch. Idit Israel

Size: 13,000 sq”m

Year of completion: 2014

Client: Kiryat Tivon Local Council, Israel.

Contractor: Sahr Khaldi.

Photography: Amit Haas.

{{item.text_origin}}