In 2009, on the initiative of Bishop Santier, the diocesan association of Créteil, supported by the Chantiers du Cardinal, opted for an ambitious project to expand the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Créteil. Conceived by Charles-Gustave Stoskopf, holder of the Prix de Rome, this architecture is typical of the 1970s when “the theology of blending-in” prevailed at the time. It is part of the contemporary heritage of the City of Créteil.

The commission was to double the capacity of the cathedral and to enhance its visibility towards the city. More than a renovation, this project involved a major redevelopment of the cathedral, giving it a new architectural lease on life from a symbolic and pastoral point of view. The new cathedral is anchored in a multicultural city, which includes five Catholic churches, ten synagogues, a mosque, a Protestant church, four Evangelical churches, a Buddhist temple and a Bahai assembly.

A dialogue between two different architectural styles, yet consistent, is established. The dome pointing skywards is based on the footprint of the original cathedral. The silhouette of the entrance, on a human scale, is now joined with the monumental proportions of the new project, focusing on the nave of the cathedral that extends from two spherical wood-clad hulls, like two hands joined in prayer that meet above the altar.

Large gatherings can be held in this new space. The existing sanctuary has been remodeled and the benches are placed in a broad semicircle. In daylight, the stained-glass window located at the junction of the two hulls shed a colored light onto the sanctuary, while at night, illuminated from inside, they become the symbol of a living Christian community.

The steeple, detached from the building on the corner of the forecourt, marks the cathedral entrance with its slender silhouette, punctuated by three bells from the old campanile. It restores the building urban scale and become a sign in the city beside the large residential buildings of the neighborhood. The view onto the cathedral forecourt is freed by opening the curtain of trees. The new square, built by the city on the opposite side, is an amenity for local residents, and an extension of parish life.

A SPACE STRUCTURED BY THE LITURGY

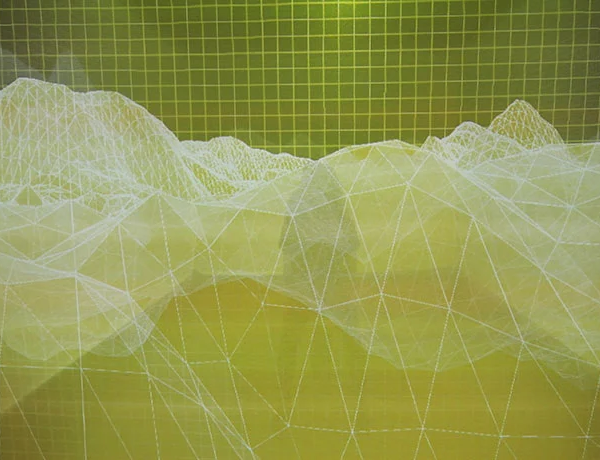

Having thus determined the architectural element of the project, we still had to determine the specifics. The new spatial organisation of the cathedral provided us with the framework we needed. The two cylindrical concrete walls that support a horizontal terrace situated about 5 metres high from the ground, become two tridimensional wooden hulls that converge at 20 metres above the altar. The liturgical axis was born from the creation of a chapel facing the sanctuary, in place of the former garden. It is marked by the presence of the baptistry. We decided that this axis, which would be the route of solemn processions in the cathedral, would become the standard for arranging all the structures: thus the supporting arches of the shells are all drawn in parallel to this liturgical axis.

This unique and particular architectural expansion is defined by the liturgical axis. The geometric complexity of the design – each arch is unique, mirrored on either side of the axis – creates a space under tension, at once static and dynamic. Each mouvement becomes a particular experience, especially through the “accelerations” of transparencies and opacities created by the progress of the arches on the spherical curve of the hulls. This architecture in motion is illustrated by the steady arch of the hanged platform at the centre of the cathedral, thus creating a long travelling.

THE WARMTH OF WOOD

The white architecture of Stoskopf serves as the setting for the new cathedral, clad all in wood, inside and out. This unity of material refers back to the ancient cathedrals, where the mass of these stone vessels was cut and chiseled by the light. This allows a straightforward reading of the two layers of the building, but most importantly, stands for unity and simplicity.

The repetition of spruce arches gives rhythm to the interior decorative style of the hulls. The intention here is not to offer an optimal structure, calculated to the finest degree, nor to display any technical prowess, but to characterise the density of a sacramental space. There are as many arches as intertwinning possibilities at the top of the dome. The boat of Peter, fisher of souls, is also suggested here.

Outside, the cladding of the hull and the steeple are also handled in wood, following the same parallel geometry of the arches. The wooden strips of Douglas fir are pre-shaded to ensure an aesthetically uniform ageing. Wood is a natural, living material, at once humble and noble. It lends itself perfectly to the design of the building’s curves. Its warmth also serves as a pattern of a fraternal community, united in the celebration of the sacraments of the Church.

AND BY THE LIGHT

Another mouvement, another axis, perpendicular to the previous one, crosses the space of the cathedral. This axis is the one of the stained glass, whose colored light encircles the space from its zenith. There is also an ascending path that rises to the source of this light: a mouvement from the altar to the two access steps to the gallery, which is extended by the curve of the stained glass. A path of light hangs vertically from the altar, climax of the composition of the Udo Zembok’s magnificent stained glass. The cross thus signs this space in three Dimensions, a space that vibrates to the rhythm of day and seasons, the orientation of the cathedral on the points of the compass — give or take a few degrees — and the positioning of the stained glass at the head of the southern hull, allowing the building to receive sunlight throughout the day.

The architectural concept of two intersecting shellshaped spatial forms celebrate a space which unfolds like a border along the interface of the two volumes. This space, designed as a glass arch, is the field of play for this commission. Spatially, the semi-circular arc opens up from east to west. As the only source of natural light the arc culminates at the zenith, vertically centred over the altar. At regular intervals, crosssection wooden ribs interrupt the continuous ribbon of glass.

Our artistic response to the given architectural shape is based on the idea that the incident sunlight artistically metamorphoses and thus should enter equally „sublimated“ into the sacred space. Paradoxically, however, light itself is invisible, because it is only perceptible to our senses when it reflects on material or flows through filters. The simplicity of the concept and composition opens up a range of different levels of understanding for the observant visitor. The spectrum ranges from our delight in chromatic filtered colours and their effects on the interior architecture of the cathedral, to the concept of the three primary colours of light, their spatial positions and the symbolism of the Holy Trinity. Undo Zembok

THE CULTURAL CENTRE

The extension of the cathedral included the creation of a cultural centre intended to offer cultural and artistic events to the Val-de-Marne’s inhabitants. A conference room and a small auditorium occupy the space originally dedicated to two multipurpose rooms. These spaces are accessible through an exhibition gallery that connects the two entrance narthexes. At its centre, a skylight allows a glimpse of the cross on the steeple. The sunlight goes trough a skylight and illuminates the entrance to each room. Near the large narthex, a bookstore café creates a friendly space at the entrance of the cathedral.

STRUCTURE AND SUPPORT

The main structure of the timber framing is composed of approximately 130 glue-laminated arches (16x75cm) ; the longest extrados arch is 26.5 metres and the smallest bending radius is 6 metres. The arches are arranged in a system of parallel beams placed 56cm from one another. The arches are jointed on the bottom by fittings, bolts and a metal axis. The coupling on the top of the two hulls is achieved by assembling alternately the northern and southern arches resting on a connecting laminated glued beam with fittings, bolts and nails. The roof deck batten is then attached directly to the main structure; the cross-laying of battens allows them to bending on the glued laminated arches.

▼项目更多图片

{{item.text_origin}}