巴西Piaba住宅 | 本土文化与现代生活的融合

One of contemporary architecture’s most pressing challenges is the maturement of a sensibility capable of deciphering the landscape on a local level, offering construction continuity with local traditions as well as the creativity necessary for accommodating new lifestyles. In that sense, Piaba House can be read as a result of a process of cultural archeology in the Chapada da Diamantina and a proposal of contemporary habitability in this landscape.

The house resulted from a constructive investigation by Lajedo Arquitetura, an office from São Paulo, in partnership with the furniture designer Leon Ades. The research on the materiality of wood and traditional joinery techniques was the common interest that inspired this cooperation. The admiration for artisanal modes of fabrication led the architects Alexandre Makhoul and Luiz Bomeny, as well as Leon Ades, to make the carpentry with their own hands, from the pre-fabrication of the structure until its assembly in the site, which is of difficult access. When studied with greater attention, the construction can be understood as a careful reading of the elements that characterize the built environment of the region.

Igatú, or “good water” in the language of indigenous populations Cariri and Maracá, went through an intense urbanization process in the second half of the XIXth century due to the discovery of diamonds in the region. The promise of enrichment in the countryside of Bahia brought an ambivalent legacy. On one side the consequences of extractivism and the mining industry, such as the silting of rivers and the destruction of native forests. Igatú’s wealth cycle, just like any other extractivist economy, exhausted itself. Most of its population left the city and today it is a small village with a population of less than one thousand. On the other side, an autochthonous culture flourished and the constitution of a regional notion of beauty, that despite its abandonment, remains rooted and alive through its few inhabitants.

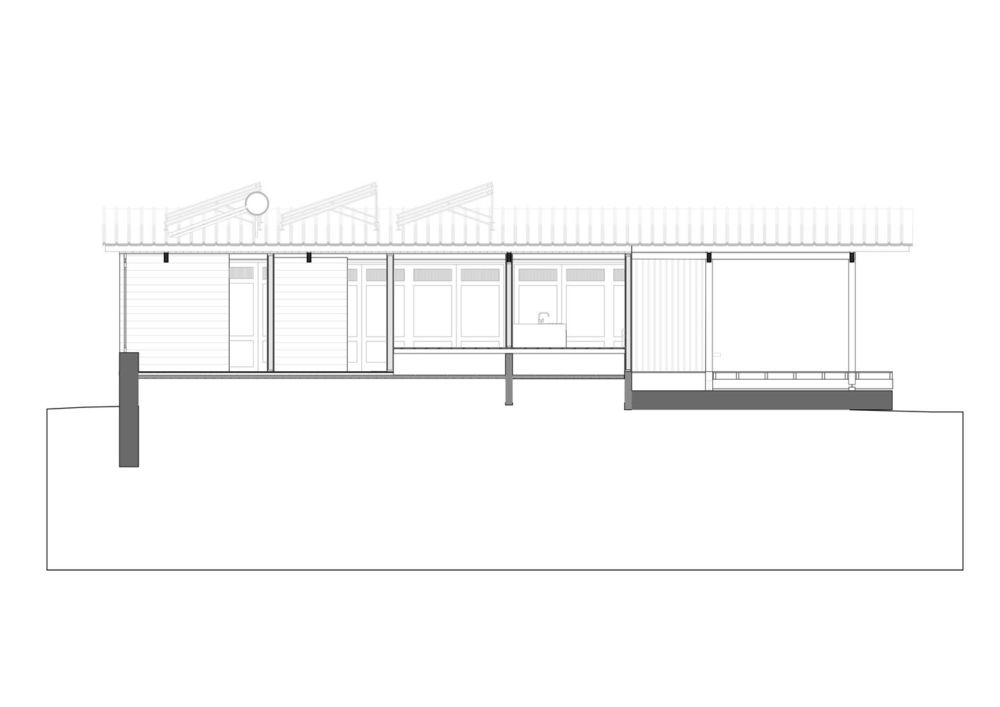

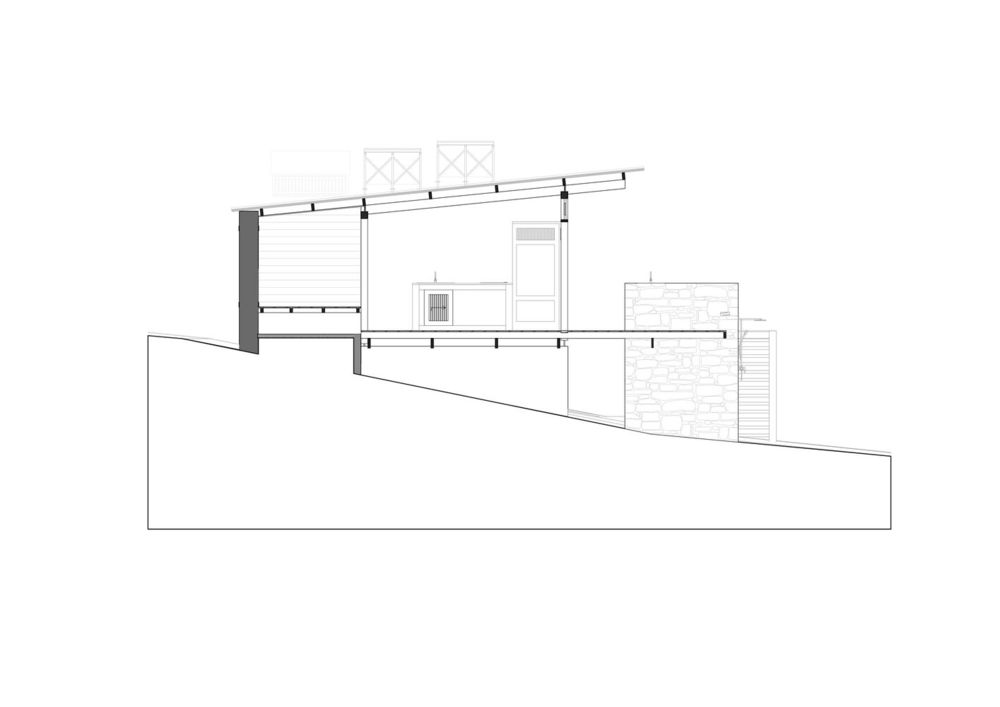

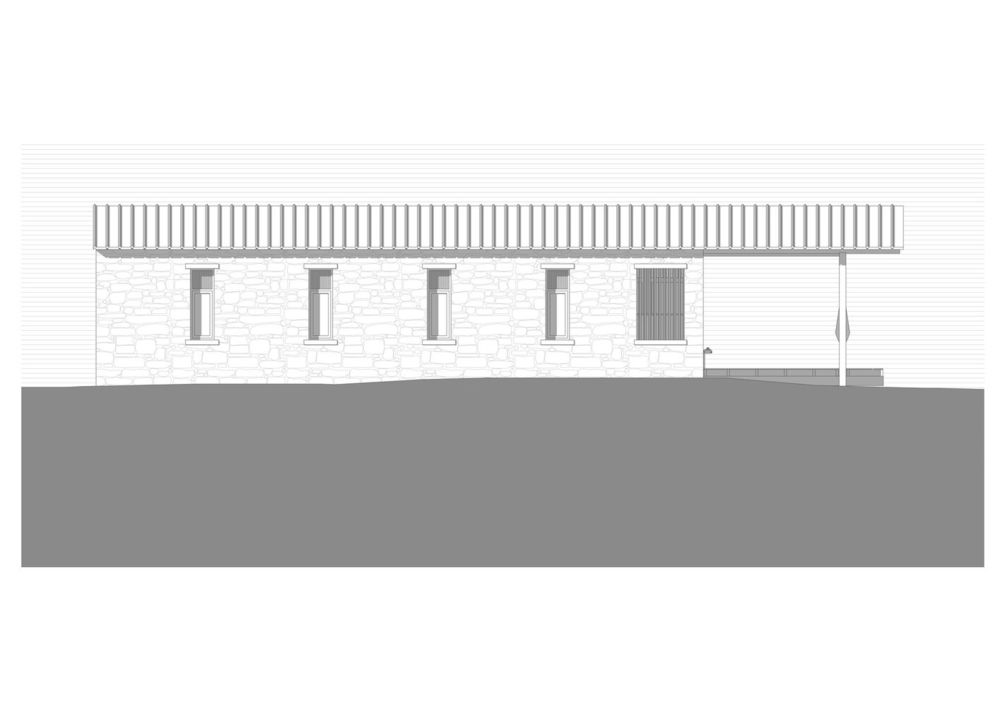

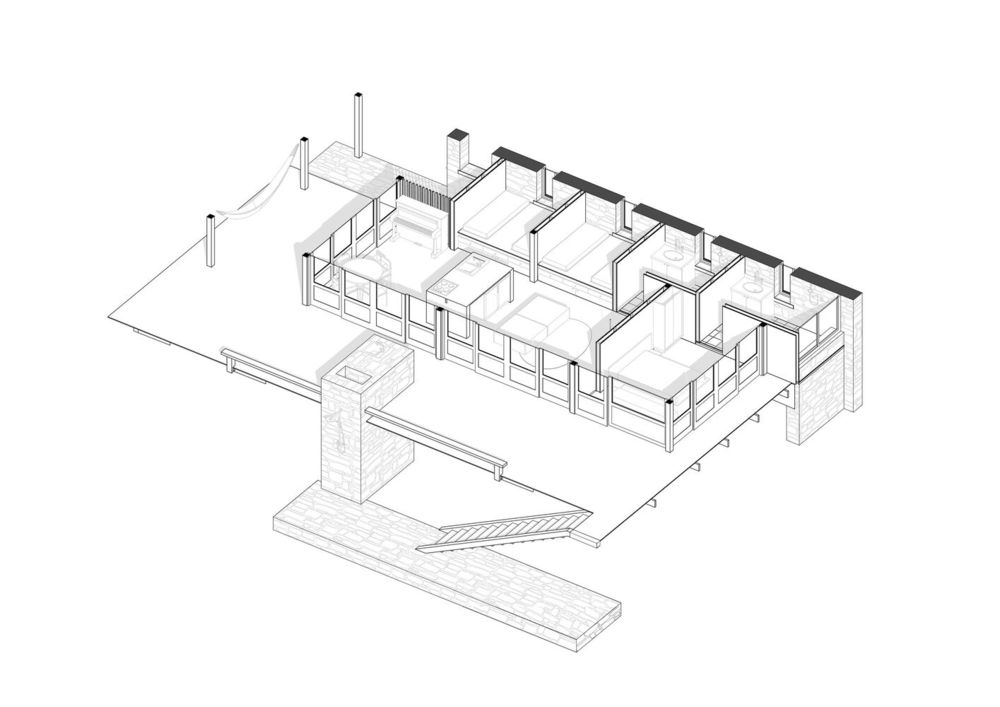

The house design seeks continuity with local construction traditions, such as traditional typologies found in Bahia’s colonial architecture and the landscape of the Chapada da Diamantina. Having as a central reference the Casa de Caminha from Portuguese architect Sérgio Fernandez, the design encrusts itself in a slope, creating an open space of acquaintanceship that blurs the frontiers between interior and exterior. When decomposed in its elements, Piaba house deconstructs colonial architecture, rearranging its elements in a new organization – adequate to the place and contemporary uses. The heavy perimetral walls of colonial Brazilian buildings, with their thin rectangular apertures disposed in regular intervals, appear here as the façade of the house – also referencing the typical frontality of colonial architecture that characterize the streets of the Pelourinho and Ouro Preto. However here the adopted construction technique isn’t rammed Earth but rather a wall in stone, typical of Igatú, with its assemblage lines developed through generations of local artisan construction workers. The patio, an essential element in Brazilian and Mediterranean architecture is also reinterpreted. Patios disseminate in hot regions as an intelligent strategy for integrating with the local climate, allowing for protected access to sunlight and the ventilation of the built volume.

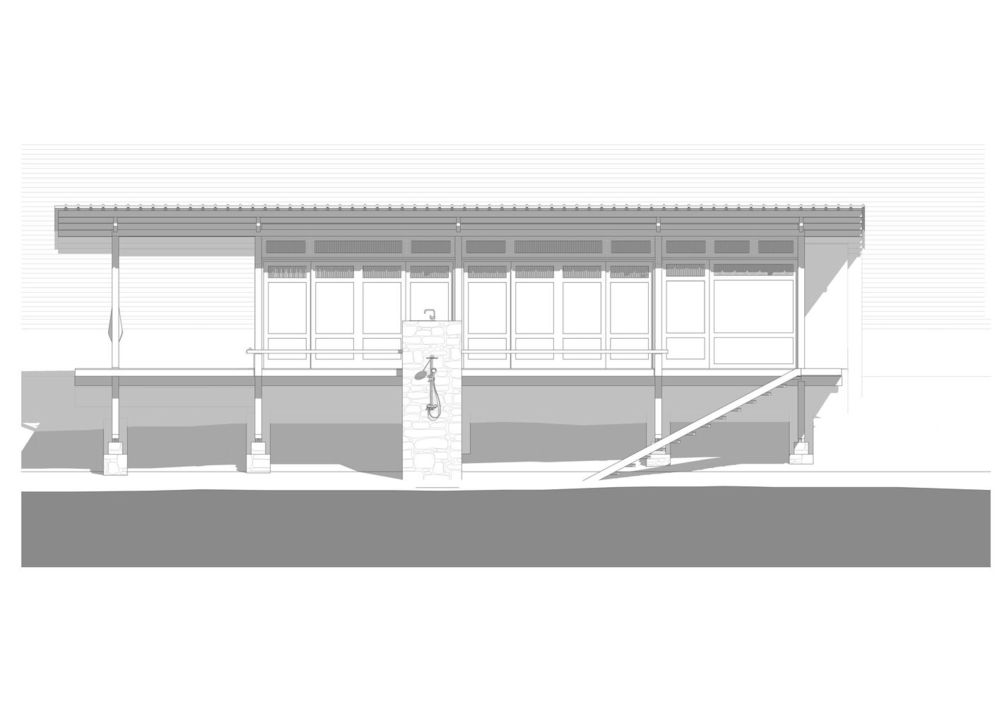

The wooden structures were fabricated in São Paulo while all other elements were fabricated and assembled in loco by the architects themselves and the team in Igatú. Experience in which they submitted themselves to guarantee an understanding of the local reality; and logistical and construction difficulties as well as the potential of the local workforce; to also feel the weight of their design in their own hands.

The foundations in reinforced concrete, the walls in stone, and the wooden windows and doors were executed by local construction workers. Throughout the building process, the architects also lived in the city, experiencing the daily reality of the construction and local life. In the plan, the project can be understood through three distinct strips. The first, along the heavy stone wall, is constituted by bathrooms and bedrooms that resemble alcoves – an intimate room design typical of Brazilian colonial architecture – closed from the living room through a curtain only. The second strip, more important architectonically, is constituted by the living room, kitchen, and main suite. The last strip is the wooden deck, open to the landscape. In Piaba House the patio, or the space, gets confused with the house interior. The exterior is built with a deck in Itaúba wood, creating an ample living area. The floor continues inside the interior, creating a continuous level. The integration between external and internal areas is not only reinforced by a continuous height through these ambients but also by the continuation of the wooden flooring. This integration is also made through the mirroring of the infrastructure nuclei. One of these is in the house interior and it composes the kitchen with a sink, fridges and a stove attached to it. The other one is on the exterior, with a barbecue grill and sink. This last nucleus complements the first one and allows for a more informal and social approach to cooking. In this external volume, there is also, on the ground level, a shower for use after a swim in the nearby river.

This relation between interior and exterior demonstrates a comprehension of the program which is not only functional but also ceremonial adequating itself to the necessities of life in this landscape. Evidence of this type of thinking is the house’s entrance hall, where the roof takes off from the heavy wall in stone, creating an entrance portico, with a height difference that can be used as a bench – where one can remove mud and dirty shoes after coming back from the woods. The quality of Piaba House is the maturity and sensibility of the architects in deciding and being able to realize a continuity with the historical antique roots of that place, creating a piece that fits adequately to the landscape. It is not a foreign element but rather a talk with the lifestyles and constructive traditions of the surroundings.