NOLISTRA Housing | 彩色城市岛屿,焕发生态活力

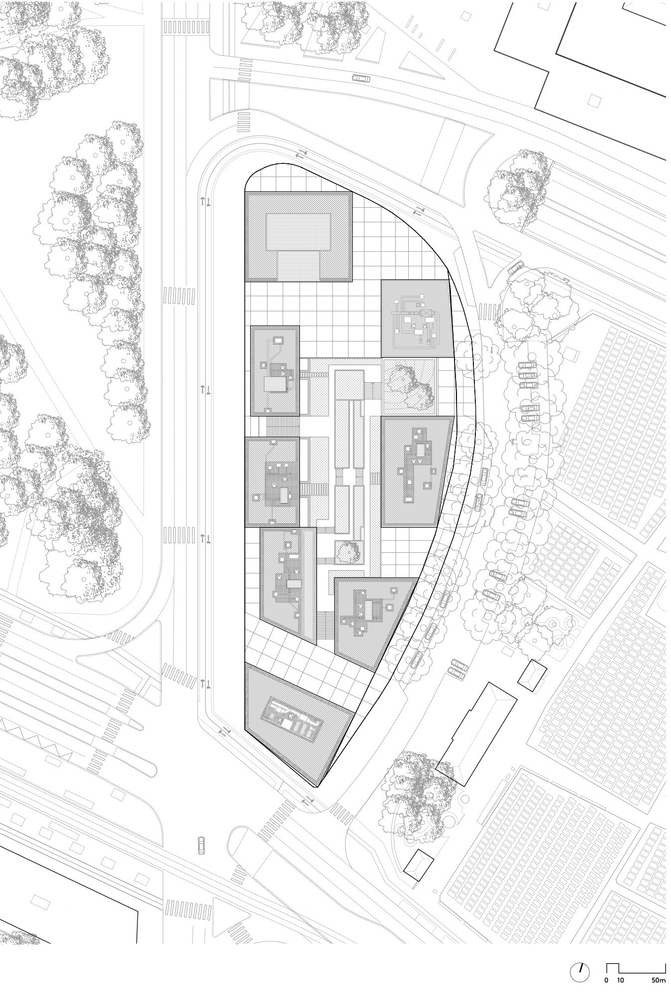

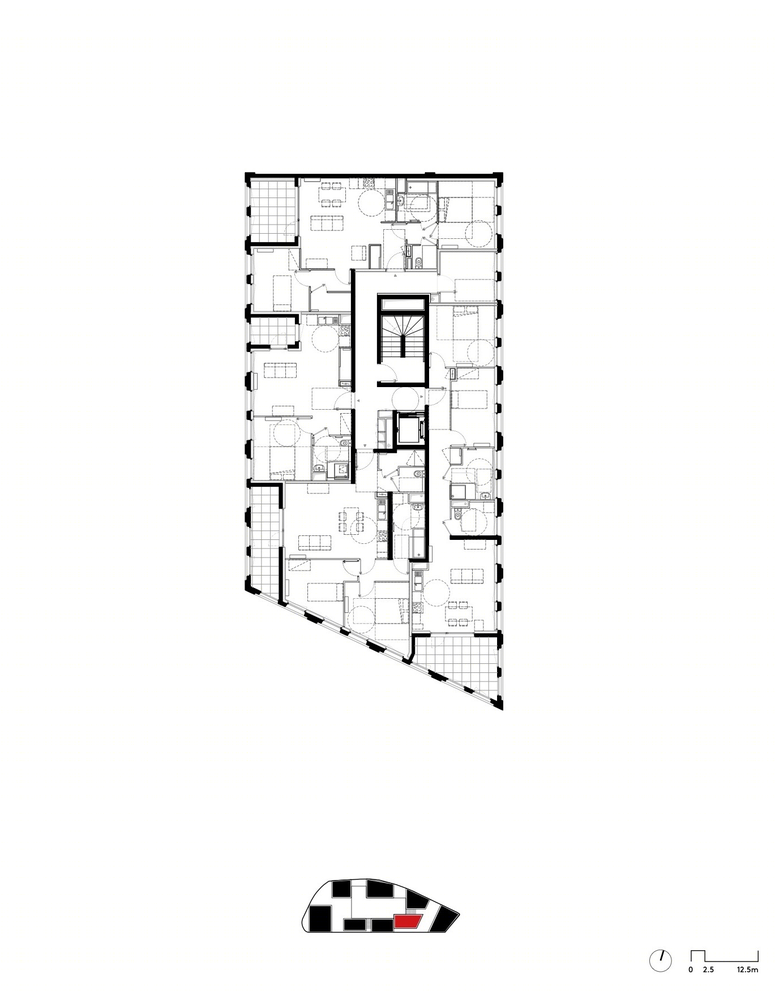

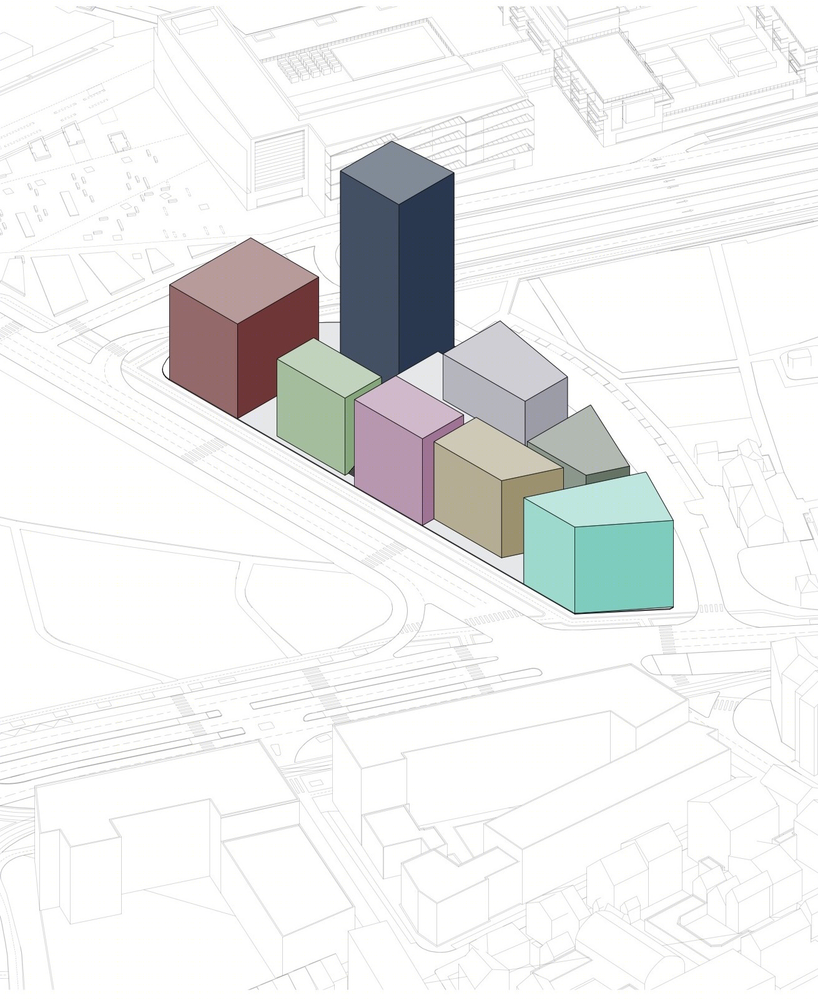

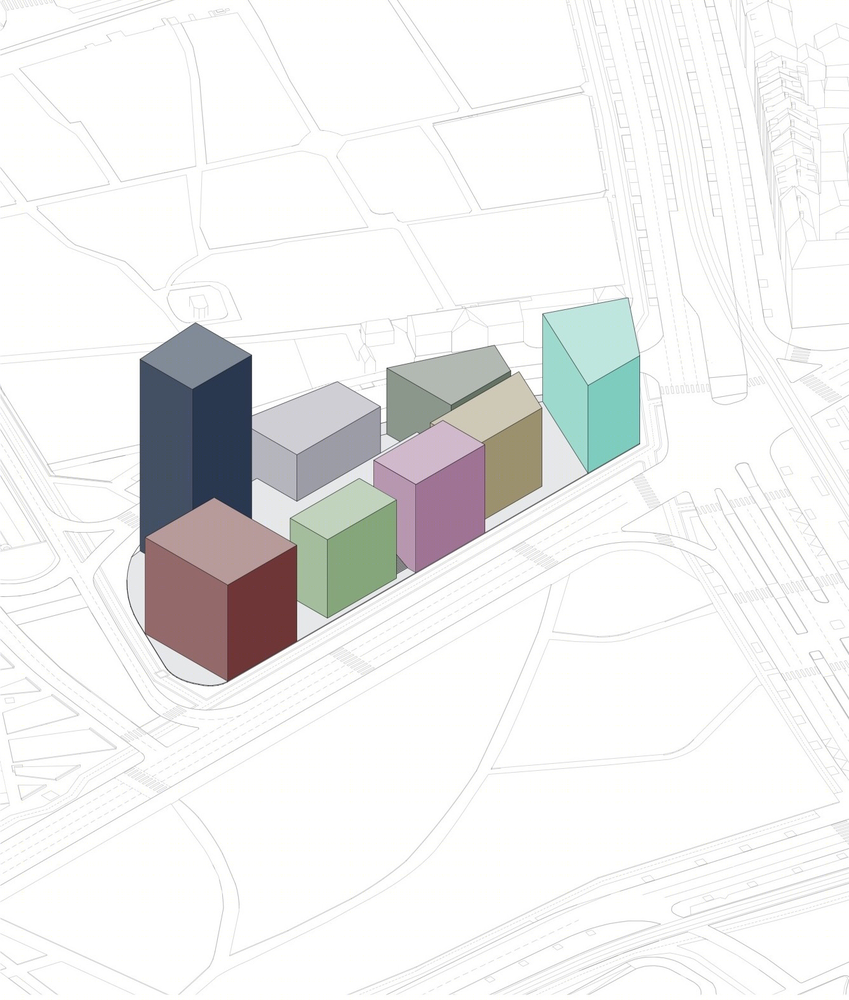

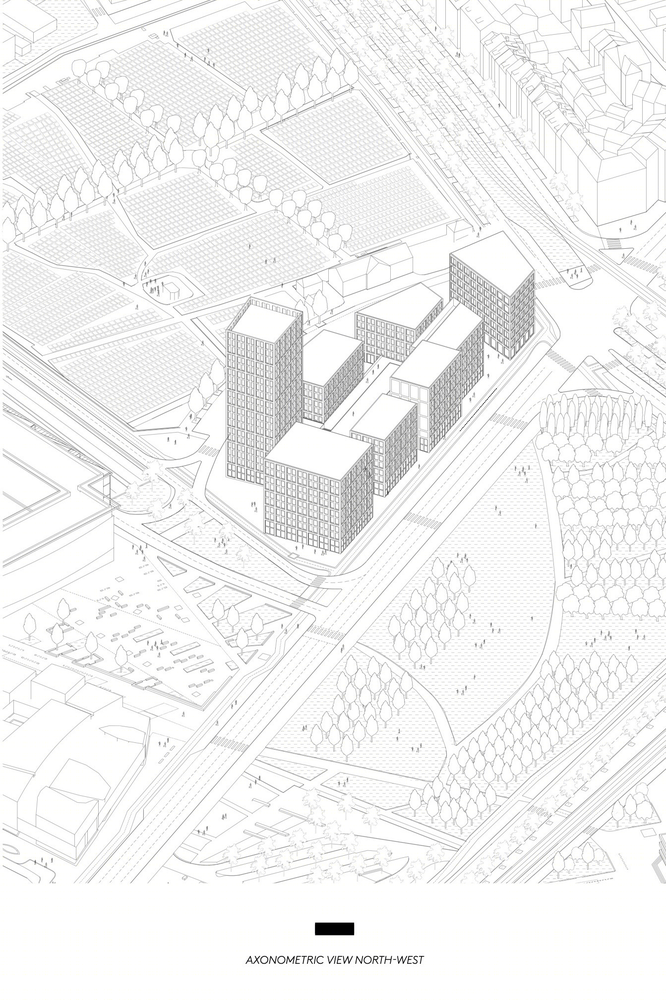

Colors over the city. The Saint-Urbain block has now completed the urban development zone Étoile in Strasbourg. Located between the Saint-Urbain cemetery and the Parc de l’Étoile, bordered on one side by the broad avenue Jean Jaurès and on the other by the cross-border road E52, the new neighborhood appears as an urban Island, a colorful emergence in the horizontality of Neudorf’s landscapes.

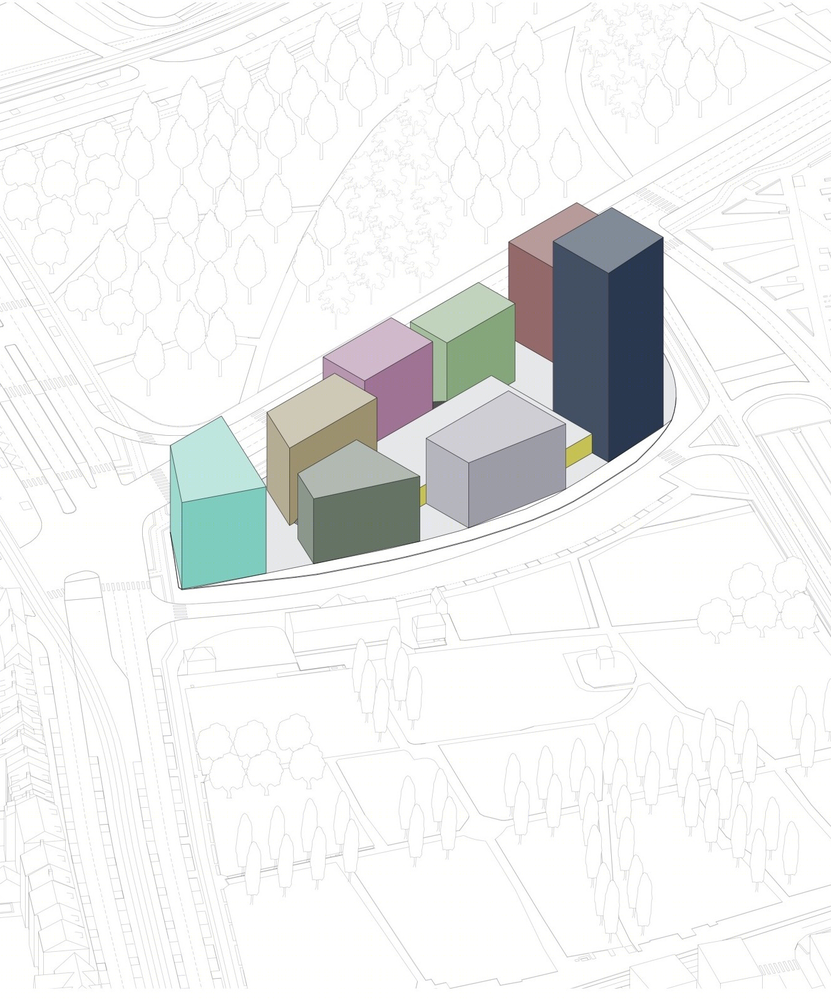

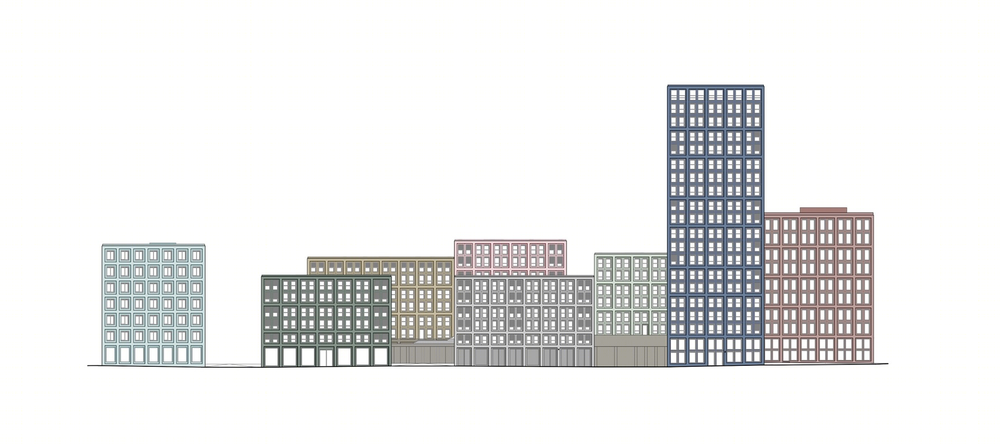

At a local scale, the project activates a major link between the city center and the Neudorf district. At the regional scale, it constitutes one of the milestones of the “Deux rives” urbanization project, which itself extends as far as Kehl in Germany. Set in this strategic position, eight buildings today embody the urban ambition of the new Euro‐metropolis in giving form to more than 21,500 m2 of a mixed real estate program, composed of 178 housing units, a hotel, offices, and commercial space. In its size and its ambition, Saint‐Urbain is a new fragment of the ecological, democratic, and lively city that is taking shape today.

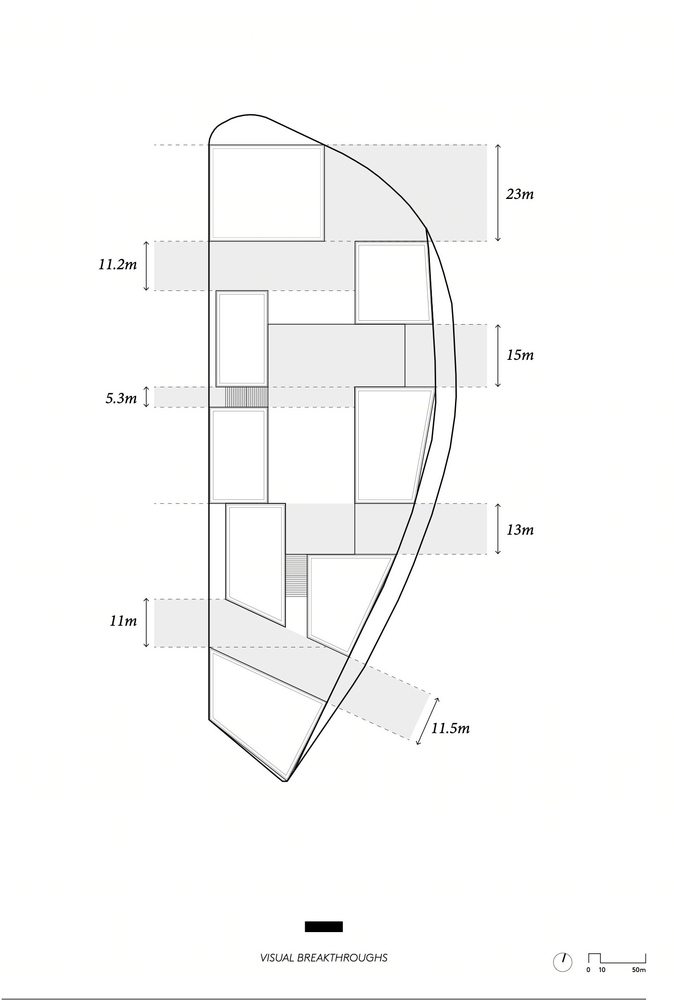

An urban island. The Saint‐Urbain block takes advantage of a condition of relative isolation in order to affirm its own identity and to generate a new intensity. It is an urban island that relies first and foremost on a complete and autonomous programmatic offer. Emerging an environment of flows, the seven volumes of the new neighborhood sit on an active base made up of food shops and essential services, distributed around a garden. It is an attractive place for work and is ideally located for urban tourism (an Aloft hotel opened there in September.) Insular, yet perfectly connected to the rest of the city.

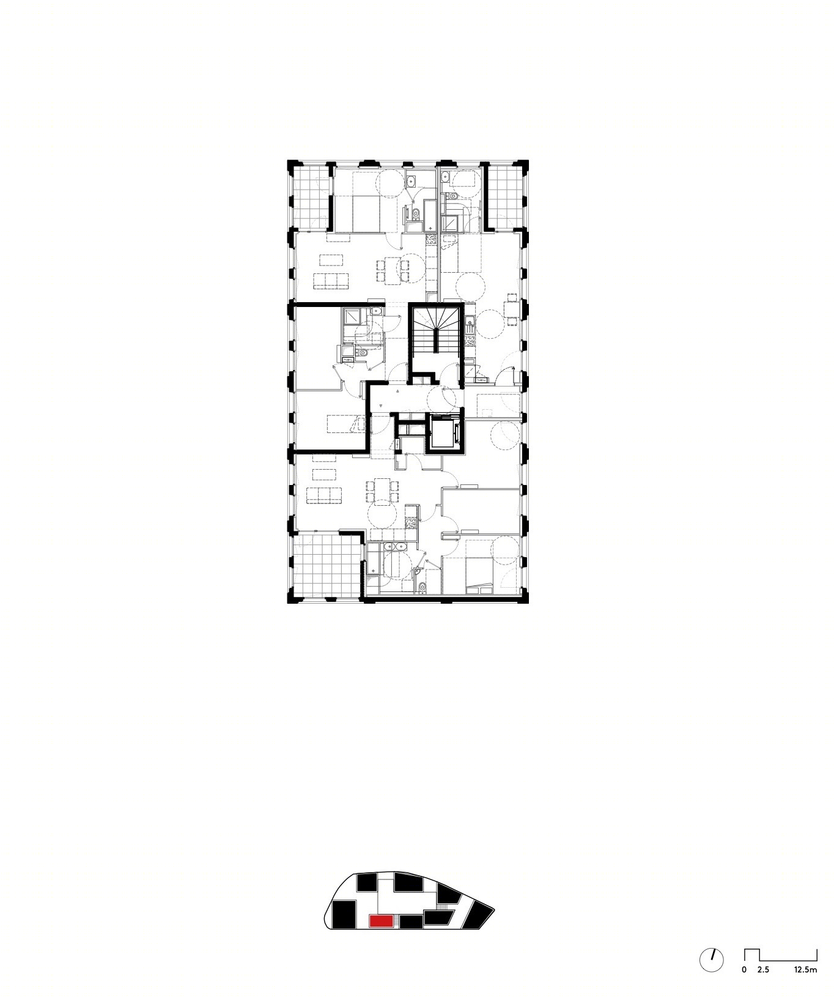

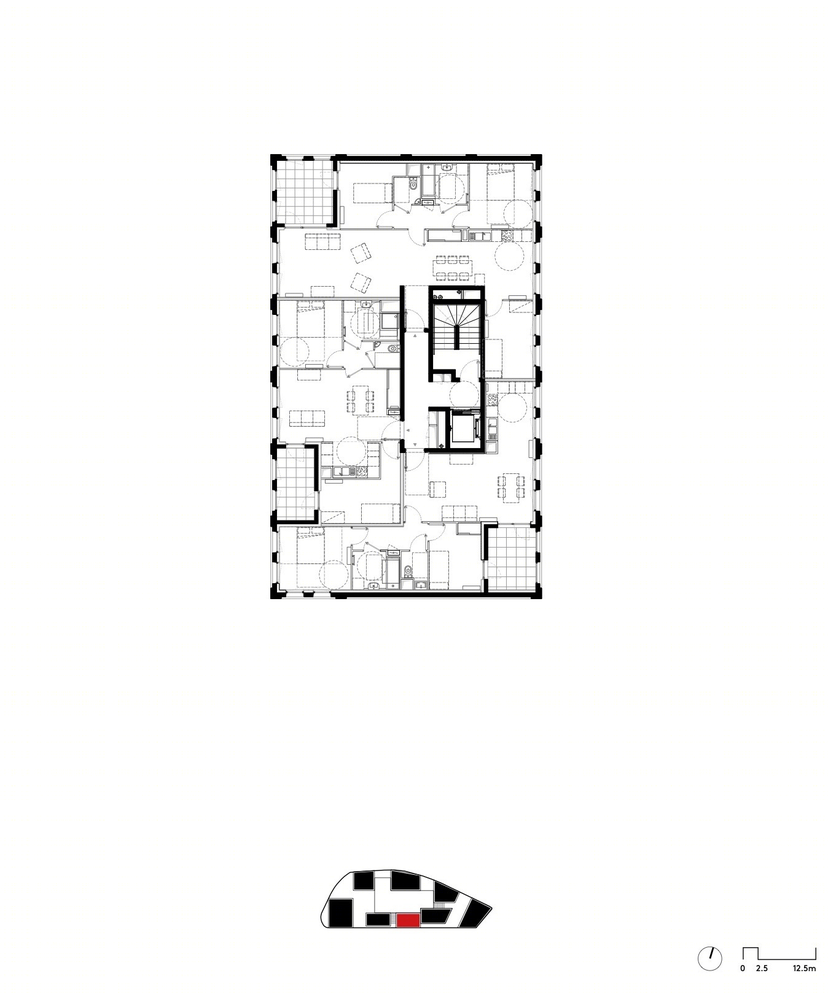

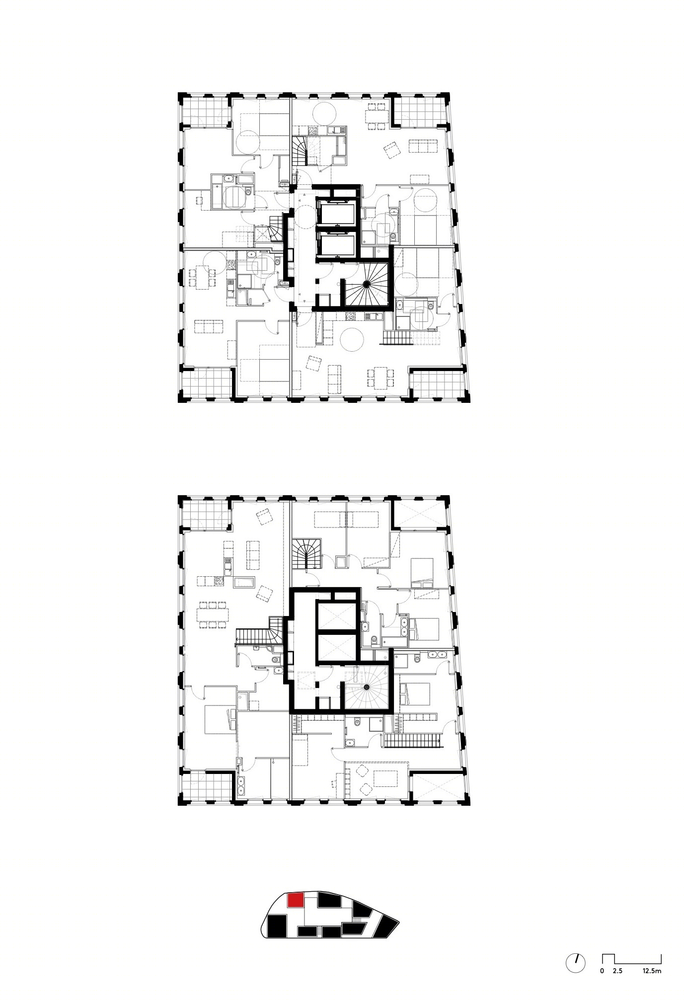

The housing – offered in terms of free, assisted, or inter-mediate ownership, or as social housing – responds to the diversity of possible living situations. If the functional diversity of the block provides energy to the daily life of its users, its residential diversity allows each individual to imagine residing there in the long term.

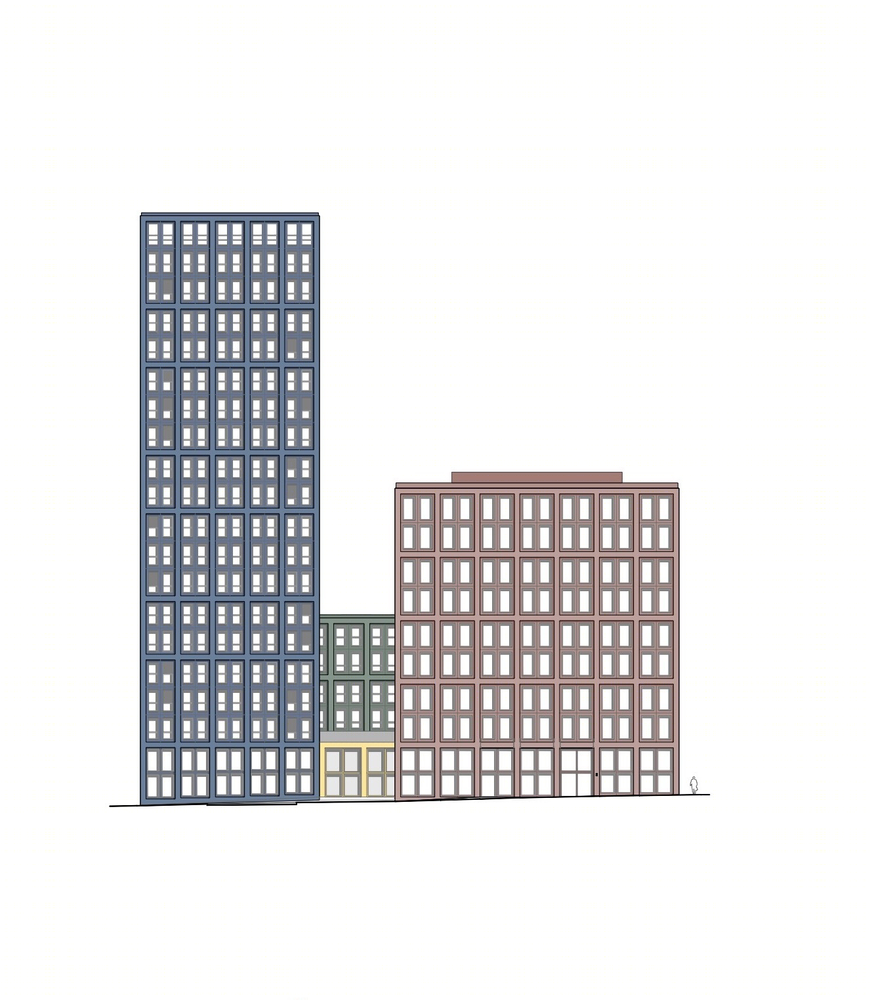

The sustainability of the buildings is a central question. Each of the buildings offers high performance in terms of energy, while still maintaining high levels of comfort. As a first architectural response to the public health crisis we’ve been experiencing since March 2020, this notion of the comfort of living spaces is a leading ambition. Large windows provide all of the housing units with ample natural light, while generous loggias complement the units as exterior extensions, both open and intimate, and necessary for collective life.

The project goes beyond (and transforms) the modernist element of the slab, staging its disappearance. Vegetation takes a central position in this strategy: all the roof terraces and the entirety of the base are planted. Beyond maximizing water retention, the principle of re‐planting the block allows for reestablishing ecologic continuities with the adjacent green spaces, the Parc de l’Étoile, and the Saint‐Urbain cemetery. It means going beyond the objectives of a performance‐based ecology and towards an ecology of well‐being, at home and in one’s own neighborhood.

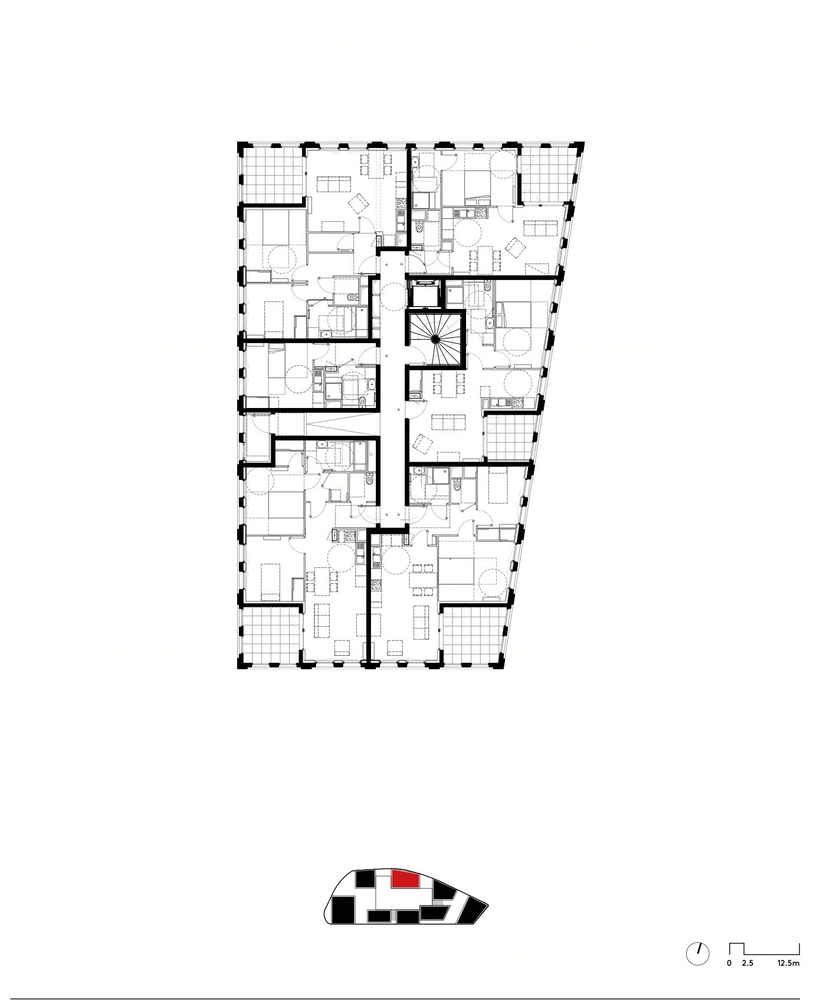

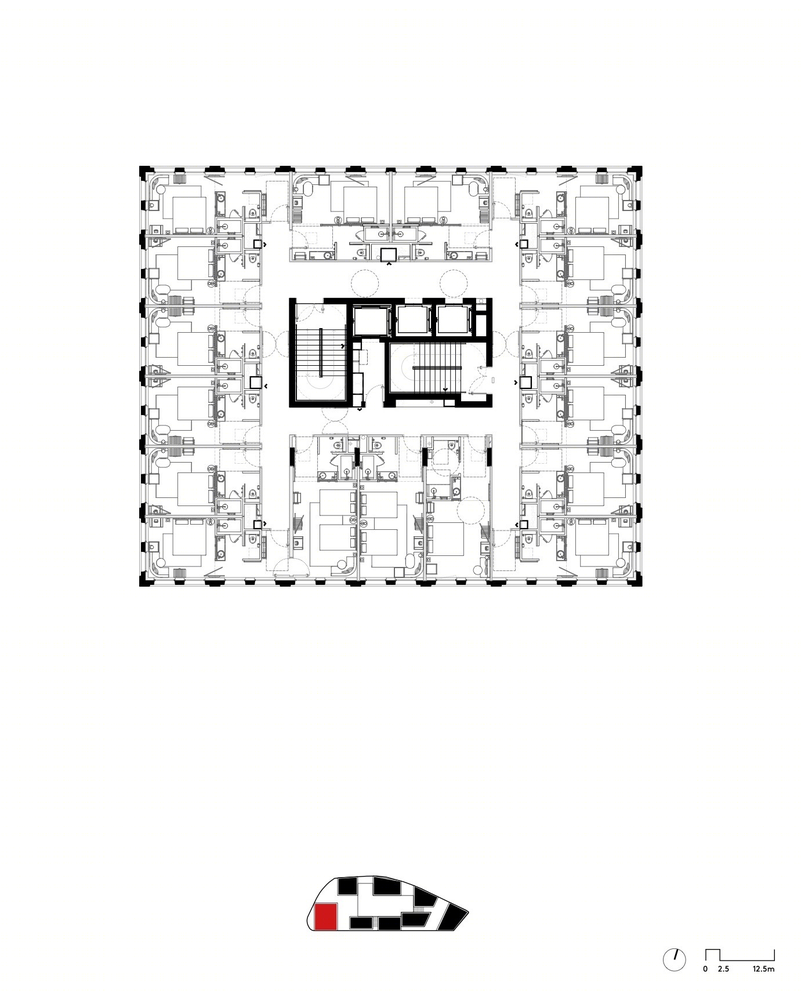

The buildings’ sustainability is also a statement of commitment. As Baudelaire once wrote: the form of the city changes, alas, faster than the heart of a mortal! Our current times wouldn’t contradict this, and the uncertainty that characterizes this era forces us to think differently about the lifespan of buildings. The construction‐related choices that guided the building of the Saint‐Urbain block thus anticipated its possible future evolutions: load‐bearing envelopes allow for the liberation of its interior spans, with rational construction leaving open all possibilities for layout and for the evolution of the program.

History of windows. Gathered around a common garden, the eight volumes of the Saint‐Urbain project together compose a dense, compact city block. The vis‐à‐vis and the adjusted spacing of the blocks contribute to the domesticity of the neighborhood and enhance a feeling of belonging. Between the visible and the hidden, both the intimacy of family life and the urbanity of collective life are played out.

The architecture here guarantees sociability of closeness while at the same time opening up to the urban landscape and metropolitan horizons. It is the experience of this specific and extremely qualitative relationship of scale that is proposed, starting from a careful reflection on the window and its repetition.

This idea of the repetition of architecture by the architecture itself is essential in this case. It is through repetition, first and foremost, that the project gathers the history of the city. The architectural forms of the Saint‐Urbain block ultimately repeat those of the past. Through the design and composition of their facades, they assemble the historic facades of Strasbourg and add new vertical pages to the Alsatian capital. The project’s architecture plays on this cultural transmission as a language in which the window would be the first word.

The architecture is also repetitive in itself. This condition aims towards a level of neutrality and plays out in the relationship between the elements composing the buildings, their structure, their profiles, and the bodies that pass through them. The window and its multiplication, in rows and columns, allows for connection between these scales of architecture and of man.

Finally, repetition is democratic. Regardless of who lives behind these walls, when seen from public space, the unity of the facades reestablishes the equality of its inhabitants as citizens.