融合传统与现代的悉尼 Machiya House

Machiya House beautifully blends old with new in a Sydney heritage setting. Inspired by the traditional Japanese townhouses (Machiya) of Kyoto, its private and public domains discreetly co-exist, with layers of screening and curated openings to draw in light and engage the streetscape. Located on a small, exposed corner site in the Iron Cove Heritage Conservation Area in Balmain, Sydney, the design sought to create a contemporary home that engaged with the street and respected its heritage. The original semi-detached dwelling suffered from a lack of light, space and disconnection with the outdoors.

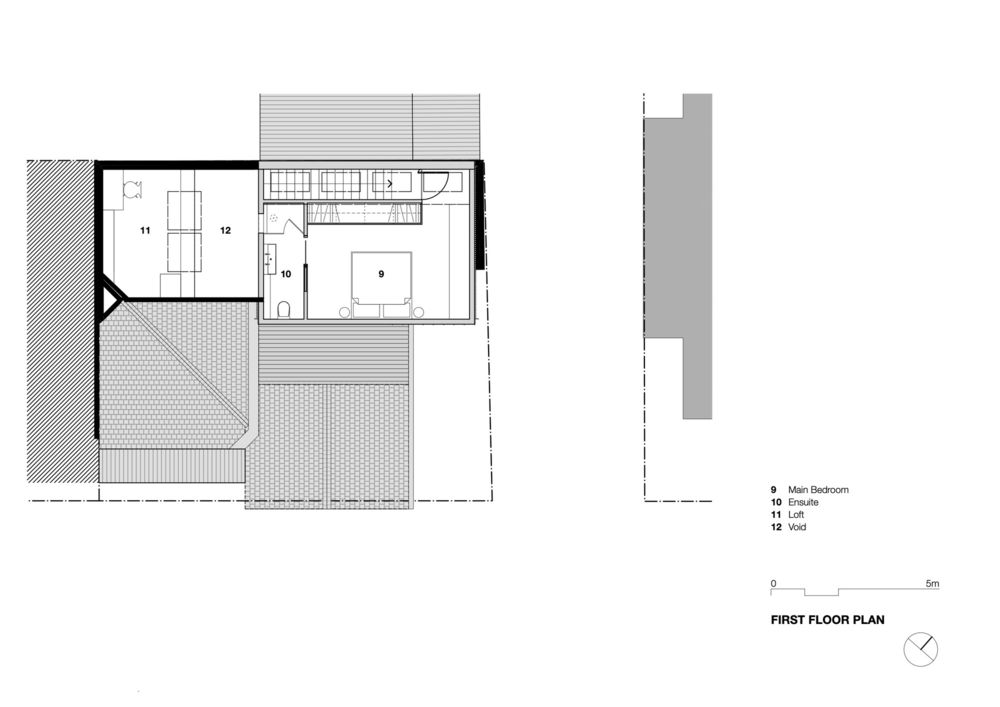

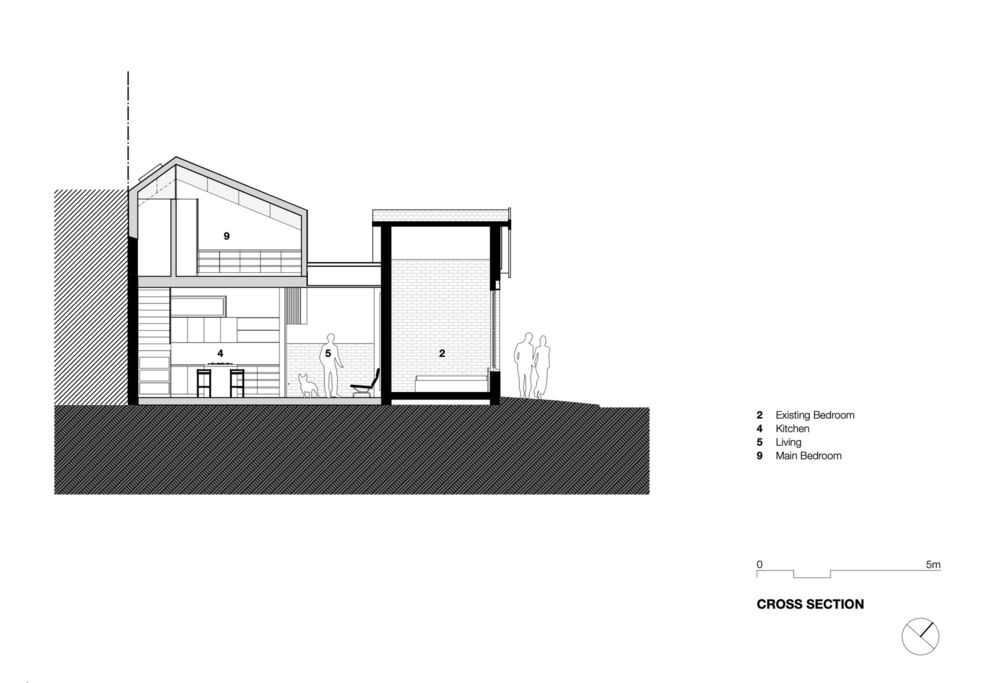

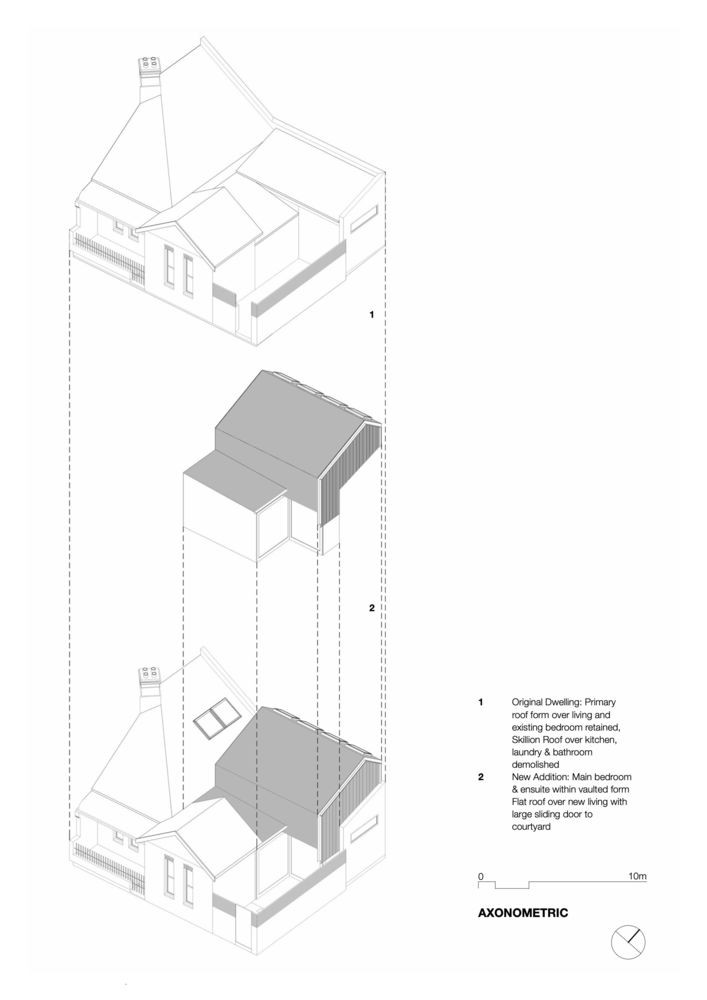

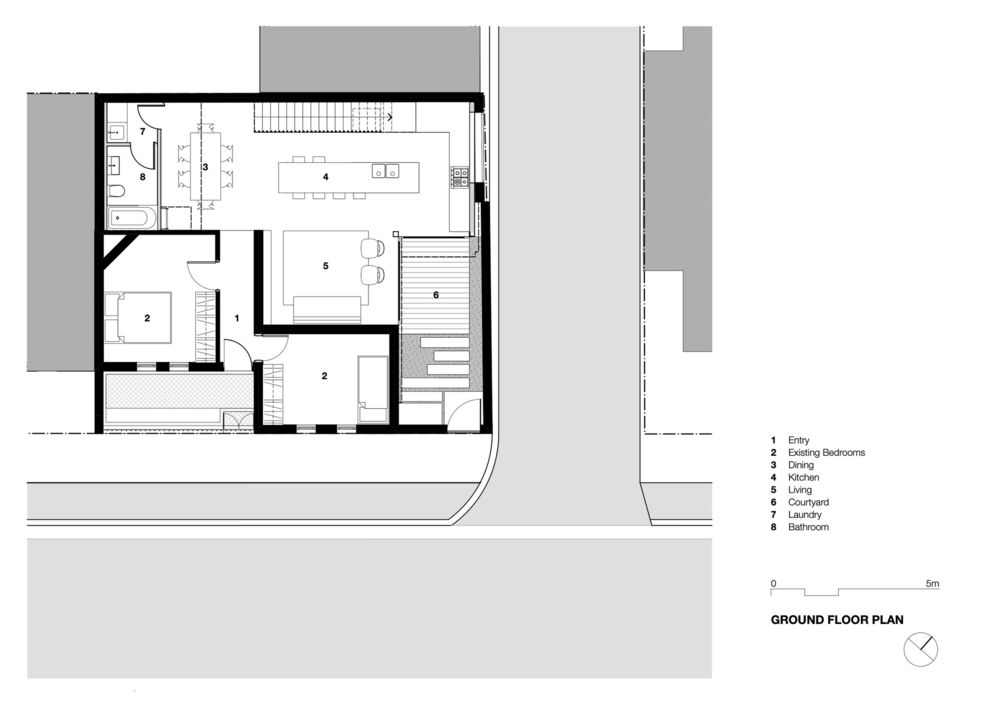

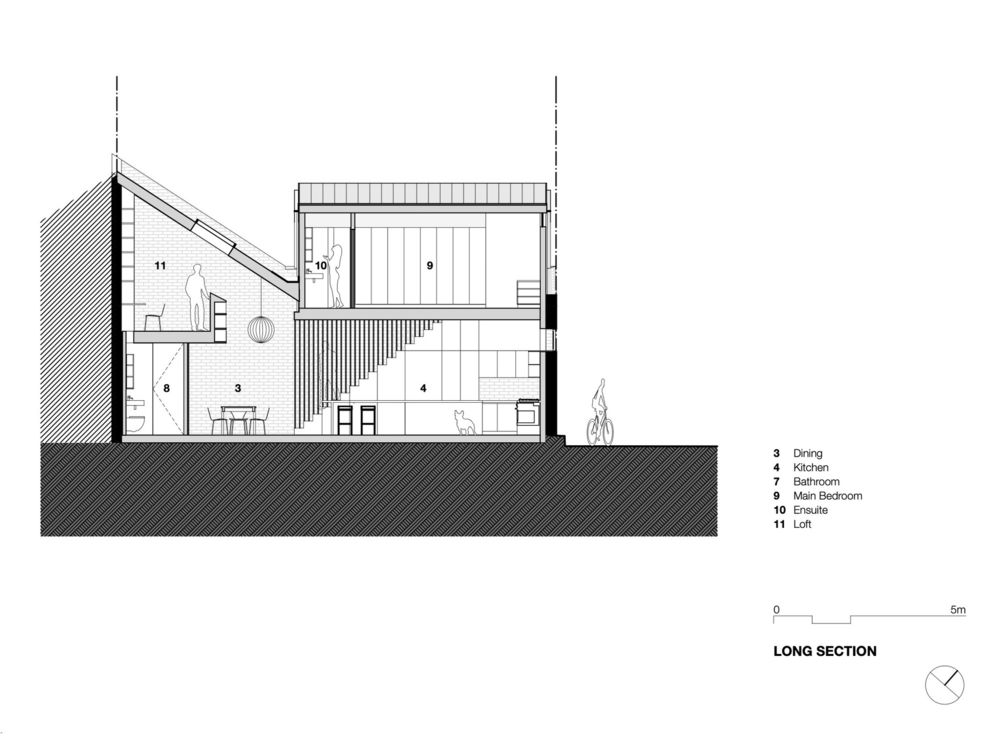

With a site area of only 117sqm, the clients desired a new master retreat, ensuite, study, and reconfiguration of the kitchen/living/ dining areas, all with minimal expansion of the building footprint. With a heritage requirement to keep the front two bedrooms and primary roof form intact, wet areas, kitchen/living/ dining areas were reconfigured within the existing L-shaped footprint to provide a seamless connection to the courtyard, while a new first-floor master bedroom and ensuite were added above. To minimize the extension of the original footprint, the new study was sleeved under the original roofline as a mezzanine loft, accessed by a ladder.

Utilizing the square site plan to best advantage, spaces unfold around a spiral path, borrowing space, light, and views from the next, providing a modicum of privacy to each but overall connection. Whilst each space is characterized as a distinct volume, they are playfully connected, spatially layered, sharing daylight, views and the element of delight. With a relatively modest budget, a robust and humble palette of materials was nominated, which required little treatment or embellishment; reveling in the beauty of the everyday. Expensive finishes and fixtures were sparingly used, while certain details like the stair and external timber batten screen were prioritized. In small spaces, fine details speak volumes.

Respecting the heritage of the area, layers and traces of the past are deliberately revealed through materiality and form. The first-floor addition discreetly recedes, echoing the original gable in form. However, from the laneway, it is animated and playful with its timber-battened screen. Retaining and exposing existing brick walls also brought environmental and cost benefits, capturing embedded carbon, and (along with the honed concrete slab) offering high thermal mass and insulation. Strategically sited operable windows and skylights enable passive cooling and heating. These curated openings, which harness daylight and draw green views deep into the interior, are equally important to the building’s engagement with the public domain.

From the main street, the new first-floor appears no more conspicuous than an attic extension, its walls, and roof wrapped in standing seam metal cladding. From the laneway, the addition is screened with a veil of hardwood battens and framed in galvanized steel – a nod to Balmain’s industrial past. At night the cedar framed windows glow, lantern-like, signaling occupation. Its layering and screening, which take inspiration from the traditional mercantile townhouses of Kyoto (Machiya) weave threads of the past into a new face that speaks of light, air and the life lived within.