规制化的院子布置完后,利用剩余的边角空间因地制宜形成的,它们构成了另一种更有活力的院落景象,体现在由于不统一的杂多布局而产生的自然美。当然这种活力也会在日常生活中走向另一种极端,那就是当每户人家都在这种杂多的布局中努力去占有更多的私人空间时,则活力反而会被混乱窒息。

In Beijing’s Hutong area, there are many courtyards formed by left-over spaces between regular Siheyuan courtyard systems. These common but dynamic courtyards represent a kind of informal aesthetics. However, this liveliness sometimes ends in chaos when residents trying to extremely occupy public space for private use.

▼改造后的雨儿胡同,Yu’er Hutong after renovation ©申立仁、王雨蒙

雨儿胡同16、18、20号就是这样的边角杂院,它是由三个院子构成的,院子的感觉并不强,仿佛是一条胡同里的胡同。在没在进行环境整治前,这条胡同里的胡同实际上是个迷宫,因为每户的私搭乱建使得公共空间变成一条极小宽度的蜿蜒的线型走道。从外人眼里看,这种曲折似乎充满了自下而上的活力,而事实上任何一个曲折都是邻居间空间博弈的结果。

The NO. 16, 18 and 20 courtyards in Yu’er Hutong belong to this kind of “left-over” type, and form a space of a Hutong within a Hutong. Before renovation, this “Hutong within a Hutong” is a linear narrow passage, like a maze shaped by alongside expanding private spaces. Every bottom-up space making, no matter how lively and lovely the visual effects are, is actually a result of spatial gaming between neighbors.

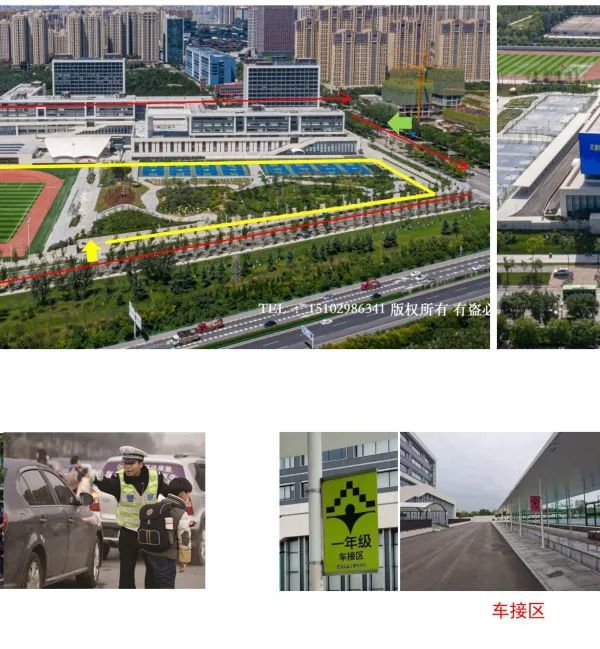

▼雨儿胡同区位,site location ©都市实践

▼雨儿胡同院落肌理演变,texture analysis ©都市实践

▼改造前的院落,courtyard before renovation ©都市实践

因此解决公共空间的问题,也部分地变成解决邻里社会矛盾的问题。尤其是在这样边角的居住空间,居民本来就是社会的低收入阶层,这里的百分之八十以上是不可能支付起其它地方高额房租的原住民,又面临着老龄化日益给他们生活投下的黯淡阴影。他们也希望院子中生活的和谐和阳光。

To solve the problem of public space is to solve the conflict between neighbors. Those low-income and aging local tenements living in the left-over courtyards cannot afford to rent another apartment elsewhere. They aspire for harmonious and sunny life in the courtyard.

▼改造后的院落,courtyard after renovation ©都市实践

在通过有限补偿的方式拆除了部分私搭乱建后,公共空间的改造有可能呈现出一种新的邻里空间景象。

After removing some illegal construction by limited compensation, the new public space would represent a better neighborhood.

▼整体改造轴测图,overall axonometric ©都市实践

第一,将院子中原本杂多的元素用统一的建筑语言进行表达,使其由散乱状态转变为聚焦状态,从而使公共空间产生凝聚力。

Firstly, systematically simplifying various elements to make the courtyard more unified.

▼院落局部轴测,partial axonometric ©都市实践

▼台明与矮墙,platform and low walls ©胡海波

▼台明,platform ©申立仁、王雨蒙

第二,通过用四棵树(其中两棵为新种植)把原来无主题的空间进行叙事化的统一,把原先妨碍交通、要绕道而过的老树,变成小院故事的记忆点,有一种历史时间的凝聚力。

Secondly, transforming the spaces around trees as gathering places.

▼院落局部轴测,partial axonometric ©都市实践

▼院落剖透视,perspective section ©都市实践

▼院内的树木成为历史的记忆点,trees recalling the memory of the courtyard ©申立仁、王雨蒙

▼利用旧有的防盗窗装点的车棚,bicycle shed decorated by recycled security window ©申立仁、王雨蒙

第三,通过平衡公共领域和私人领域利益的对立统一,尽量激励每户自发地美化门前的半私人空间,使居民的参与变成邻里关系的凝聚力。

Thirdly, balancing the benefit between public realm and private space. These design strategies encourage residents to maintain their own front door environment well, and to participate in public commonwealth actively.

▼改造后院落里的邻里生活,life in the courtyard afterrenovation ©申立仁、王雨蒙

▼邻里间的日常交流,communication in the neighborhood ©申立仁、王雨蒙

另一个关于社会学的设计策略在重建、补建的新房中,我们有意做了适合年轻单身的小户型,希冀招租能对院落空间的日常维护和改善有担当的年轻人,来稀释这里的老龄人口密度,带来新生活的活力。

Another social experiment is to provide small units for young professionals in the new houses, so as to introduce young people’s lifestyles to vitalize this aging community.

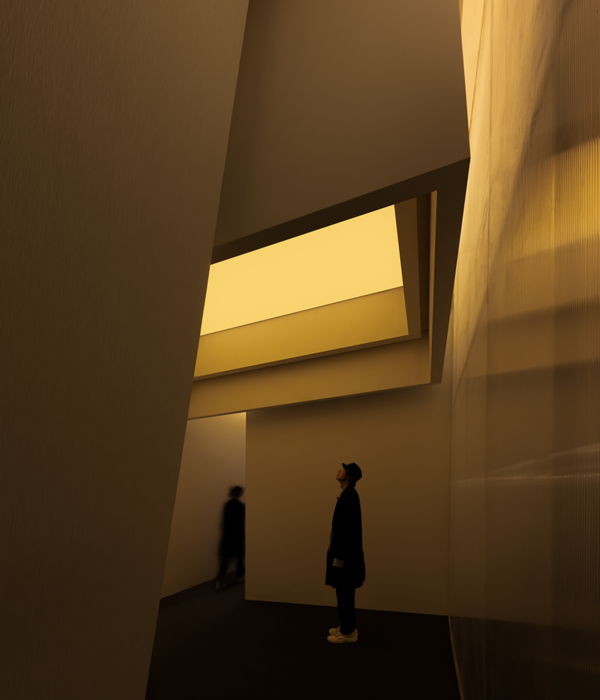

▼新建建筑中满足年轻人居住的生活空间,space for young people in the new buildings ©都市实践

▼室内剖透视,perspective section ©都市实践

这个院子的设计,是通过对普通的一砖一瓦的精心铺砌,呈现出对日常生活的礼赞。工法上,砖的组合方式所显示出的手工匠意,给空间带来精神上的温度。色彩上,用红砖加杂进灰砖,也表白了这个杂院的身份,给空间带来生活的温度。布品上,旧的石门蹲、私家花盆、老物件、晒衣杆等被揉合到新的系统中,呈现出包容性做为大杂院视觉活力,给空间带来了日常的温度。建构上,植入框架式的构筑物,和邻居家的后墙对话,并形成胡同里的核心空间,给空间带来邻里的温度。

The design philosophy is to celebrate the everyday life by careful craftsmanship with simple daily materials. In techniques, the masonry work represents the hand making and brings spiritual warmness to the space. In color, the combination of red bricks and grey ones represents the characteristics of the courtyard and brings living warmness to the space. In details, the tectonic solution to combine the old with the new brings design warmness to the space.

▼旧的石门蹲和拆下来的窗户,restored stone foundation and recycled window frame ©胡海波

▼雨水管和雨链,downspout and rain chain ©胡海波

大杂院中公共空间的再规划,为原住民带来了生活和身份的尊严。这种设计的基石是设计师对日常生活中矛盾的观察,对日常生活中习惯的尊重,和对日常生活中模式的升华。这个胡同中胡同的最终设计成果,也是项目设计师零距离、不间断地与原住民交流的结果。无论如何评价这样的成果,它表达了当代设计师对大杂院这种空间形态的善意愿景。

The public space design in these “left-over” courtyards is to restore the dignity and decency of the residents. It is based on our careful observation of their everyday life, with the respect of their lifestyles. The final achievement of redesigning this “Hutong within Hutong” is also resulted from continuously face to face communication between architects and local residents. It is our good will to have a visionary solution for keeping the vitality of everyday in this sort of courtyards.

▼院落路口,paths in the courtyard ©申立仁、王雨蒙

▼改造后院内儿童的玩乐,children playing in the renovated courtyard ©申立仁、王雨蒙

▼模型照片,model ©都市实践

▼平面图,plan ©都市实践

{{item.text_origin}}