With its gleaming white walls and elegantly terraced roofs, it is easy to forget that Himeji Castle was built as a fortress . Standing on two hilltops in the city of Himeji, the old fortress, also known as Himeji-jo, is the greatest surviving example of Japanese castle architecture from the early years of the Shogunate, which governed the island nation from the late 1500s to the 19th Century. Although never tested in battle, the castle’s elaborate defensive measures represent the best strategic design the period produced. While these measures have since been rendered obsolete, the same cannot be said for the castle’s soaring, pristine aesthetic, which earned it the nickname Shirasagi-jo – “Castle of the White Heron.”

Much of Japanese history vacillated between periods of factional and unified Imperial rule. During the 16th Century, the daimyo Oda Nobunaga began to conquer and consolidate the disparate shogunates of the archipelago into a single state, a process continued by his successor, Toyotomo Hideyoshi. Hideyoshi was as shrewd as Nobunaga was tactical, and by 1590, all of Japan was united under his nominal authority; however, without a sufficient political structure to truly hold sway over the islands, many regions were entrusted to the direct control of the local daimyo.[1]

Under Nobunaga and Hideyoshi’s reigns, Japan entered its Azuchi-Momoyama period, named for two castles built respectively by the two leaders. It was a time of sumptuously gilded wall paintings, elaborate folding screens, and the rise of the Japanese tea ceremony. The spread of castles across the Japanese archipelago between 1580 and 1630 remains one of the most prominent remnants of this cultural epoch, with many of the cities that formed around evolving into provincial capitals. When Hideyoshi died in 1598, rule over Japan passed not to his son, but to rival daimyo Tokugawa Ieyasu, who subsequently appointed his brother-in-law Ikeda Terumasa as governor of the western provinces. It was in 1609, at the height of the Azuchi-Momoyama period, that Terumasa chose Himeji as his seat of power – and set about creating a castle worthy of the city’s newfound status.[2,3]

The first iteration of Himeji Castle was built in 1346 by Akamatsu Sadanori, who sought a bastion against other daimyo during a previous period of political instability. Oda Nobunaga later gave the fortress to Hideyoshi in the 1570s, upon which it was expanded and formed into a proper castle. This was not enough for Terumasa, however, who patterned his renovations after Nobunaga’s castle at Azuchi. The grandiosity of his vision was matched by the sheer effort necessary to bring it into being: over 2,500,000 man days of labor went into the construction of Terumasa’s new Himeji Castle.[4]

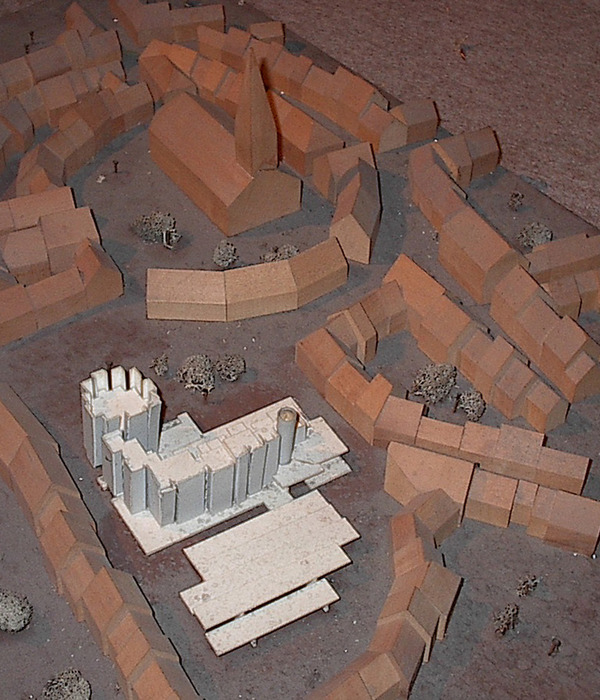

The complex built by Terumasa between 1601 and 1609 stretched far beyond the central donjon (fortified tower): like many European castles, Himeji sat within a series of concentric moats and compounds, some of which encircled and protected parts of the city beyond the castle itself. Passage from the outer compound, the Sannomaru, to the inner Ninnomaru compound is achieved through the Hishi Gate, the only portal in the outer wall. Despite its enclosure, the Ninnomaru is elegant and spacious, with a large rectangular pool known as the Sangoku Moat and a wide, verdant garden space called the Nishi-no-Maru (“West Bailey”), from which one has an excellent view of the castle’s main tower.[5.6]

Secluded behind another, higher wall, the innermost compound—the Hommaru—is made almost inaccessible by narrow, twisting paths leading to a second set of gates. Inside the Hommaru stand the central keep, the Daitenshu, flanked by three smaller towers.[7] Whereas Hideyoshi’s original keep had been three stories high, Terumasa’s rose five stories, housing six floors and a basement level. The heavy stone basement provided storage for food and armaments, and also protected a well; the floors above comprised living spaces and vantage points from which defenders could shoot arrows out the narrowly-slitted windows that helped to shield them from their attackers. A pair of wooden columns rise from the foundations to the roof, providing extra structural support to the entire tower.[8,9]

Himeji Castle is known as much for its beauty as it is for its defensive ingenuity, and it is fitting that many features meant to improve the latter are also responsible for the former. (This is not to say that its attractiveness was a fortunate accident; given that castles like Himeji-jo were highly visible from the surrounding urban fabric, Terumasa and other daimyo spared no expense in adorning their fortress homes with the finest craftwork and ornamentation.)[10] The winding path through the Ninnomaru, while picturesque with its cherry trees and changing vistas, was meant to confuse and slow invaders. Small openings in the walls lining the path would allow defenders to bombard their enemies with anything from boiling water to deadly projectiles. The gates, including the lavish Hishi Gate, were built with narrow openings to impede the progress of large groups.[11] Even the pristine white walls were a defensive measure: coating the wooden structure in plaster helped to protect the building and its occupants against fire, as did the ceramic roof tiles. With this combination of tactical circulation and defensive materials, Himeji Castle was not only an elegant palace – it was an almost impregnable fortress.[12]

Although Himeji Castle was perhaps the climax of Japanese castle design, it was never to see battle or conflict. The establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate precipitated a long period of relative peace within Japan, obviating the need for a fortress to defend against other daimyo.[13] The shogun’s 1615 edict that there should be only one castle per province resulted in the destruction of many similar buildings throughout Japan; Himeji Castle remained one of the approximately 170 to survive and, like its counterparts in other provinces, served as the administrative and commercial center of the region.[14] The castle flourished in this role for three centuries, until the end of the Shogunate and the rise of a new national government in 1868. Having never been attacked, Himeji Castle remains largely as it did upon its completion in 1609; although a fire destroyed the daimyo’s living quarters in 1882, subsequent preservation efforts since 1934 have meticulously restored what remains of the complex.[15] Relatively unspoiled by time, the shining white Himeji-jo continues to dominate the hilltops of Kansai Province, a reminder of Japan’s tumultuous past.

References [1] "Japan - Early modern Japan (1550-1850)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. [access]. [2] “Japan - Early modern Japan (1550-1850)." [3] Cowan, Henry J., and Trevor Howells. A Guide to the World's Greatest Buildings: Masterpieces of Architecture & Engineering. San Francisco, 2000: Fog City Press. p73. [4] McNiff, Gregory. "History." Columbia University. Accessed April 19, 2017. [access]. [5] "Himeji Castle, Himeji, Japan." Asian Historical Architecture: A Photographic Survey. Accessed April 21, 2017. [access]. [6] "National Treasure, World Heritage, Himeji Castle." Himeji City. Accessed April 21, 2017. [access] [7] “Himeji Castle, Himeji, Japan.” [8] Wilkinson, Philip. Great Buildings. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. p128-130. [9] Cowan and Howells, p73. [10] “Himeji Castle, Himeji, Japan.” [11] McNiff, Gregory. "Military Design." Columbia University. Accessed April 19, 2017. [access]. [12] Wilkinson, p128-130. [13] “Himeji Castle, Himeji, Japan.” [14] Mitchelhill, Jennifer, and David Green. Castles Of The Samurai: Power And Beauty. New York: Kodansha USA, 2013. p67. [15] "Himeji-jo." UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Accessed April 18, 2017. [access].

▼项目更多图片

{{item.text_origin}}