伦敦 Brunel 建筑 | 现代与历史的完美融合

Architects:Fletcher Priest Architects

Area :31248 m²

Year :2019

Photographs :Dirk Lindner, Jack Hobhouse, Raluca Ciorbaru, Tim Fallon

Manufacturers : KEIMKEIM

Structural Engineer :Arup

Transport :Arup

Quantity Surveyor :Arcadis

M & E Consultant :Cundall

Landscape :Plincke, Barton Willmore

Project Manager :Gardiner & Theobald

Main Contractor :Laing O'Rourke, Laing O’Rourke

Client : Derwent London

Cdm Coordinator : Jackson Coles, HCD

Approved Building Inspector : MLM

Façade Specialist : Arup

Approved Building Inspector : MLM

City : London

Country : United Kingdom

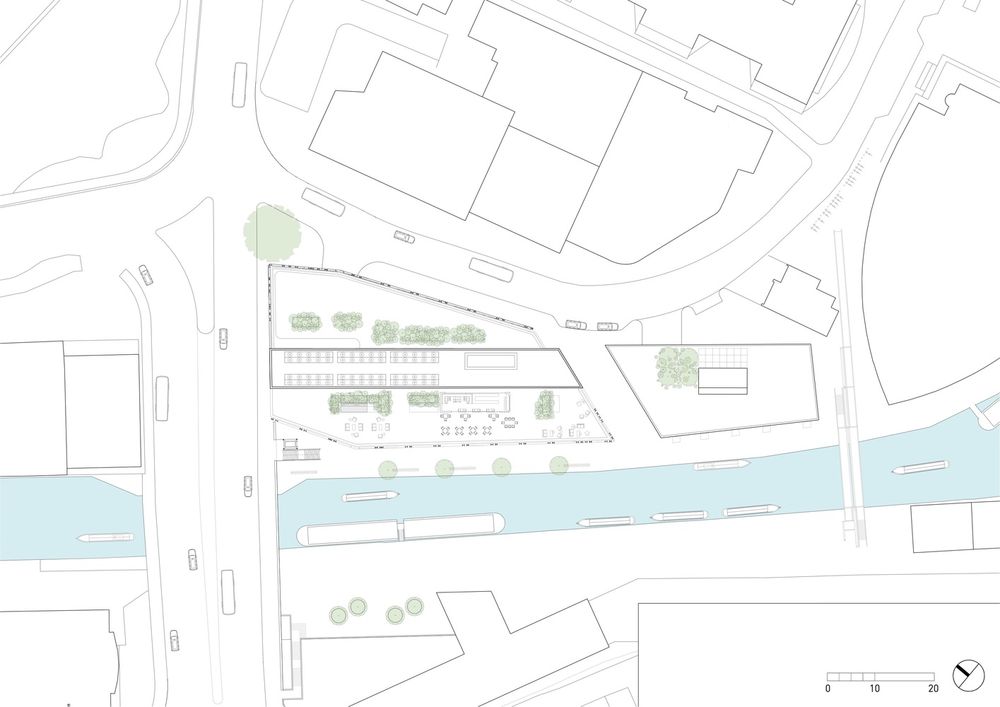

There can be few areas in London where so many engineering landmarks rub shoulders. Derwent London’s Brunel Building, a 17-storey new-build workplace building designed by Fletcher Priest, overlooks the Grand Union Canal and Paddington Station, the London terminus to the Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Western Railway, and is next to the site of Brunel’s first-ever bridge. The elevated A40 expressway runs past and the Elizabeth Line, the new cross-London railway, stops near-by. One hundred-year-old cast-iron subway tunnels run beneath the site.

This unique and evocative context sets the tone for the design of Brunel Building. The brief called for development with an innovative workspace that would attract occupiers, as well as highlighting the significance and amenity of the area. “We agreed that the design demanded a robust construction which would embody the spirit of the great engineer Brunel”, explains Derwent’s Simon Silver.

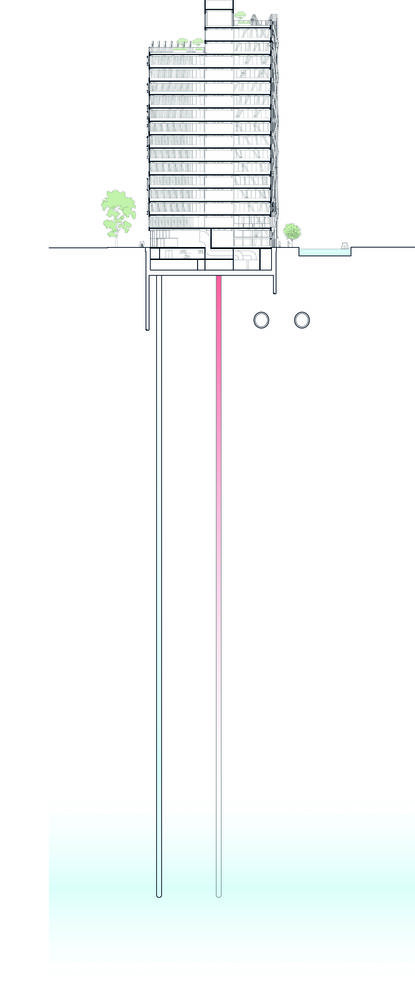

The solution was also technically driven by the presence of the canal and two Bakerloo Line underground tunnels running across one corner of the site. Working with Arup, Fletcher Priest’s proposal for a steel diagrid exoskeleton refers to Brunel’s now lost Great Western Railway viaducts. It is not only visually arresting but allows the building to span the tube lines. The building is pulled back at this corner to reduce loading, while a line of piles between the two tunnels helps to distribute foundation loads.

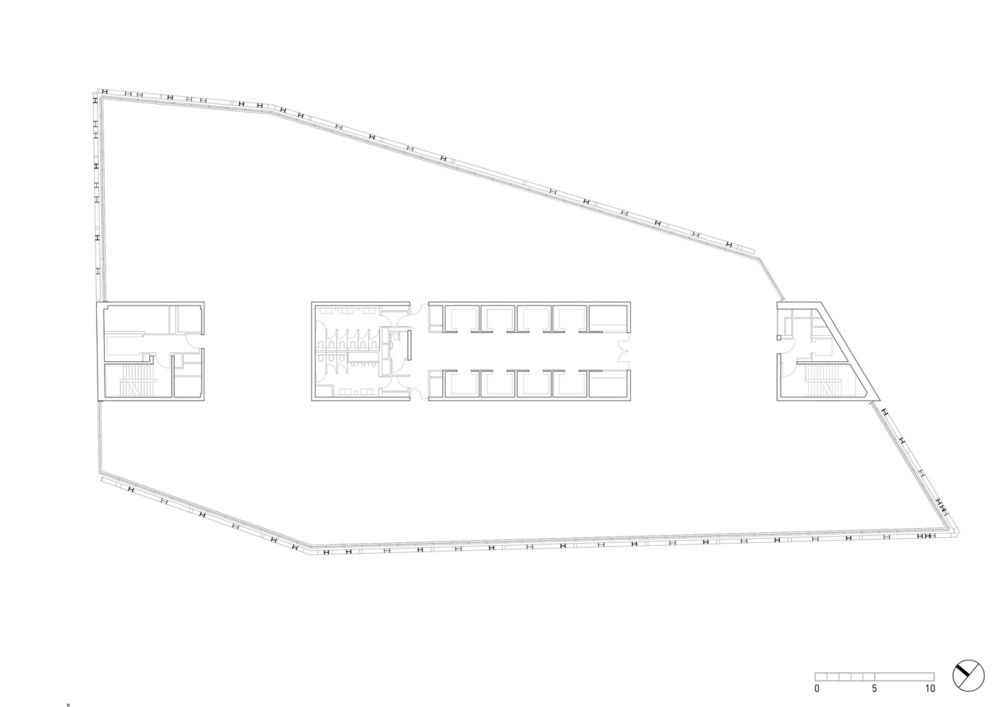

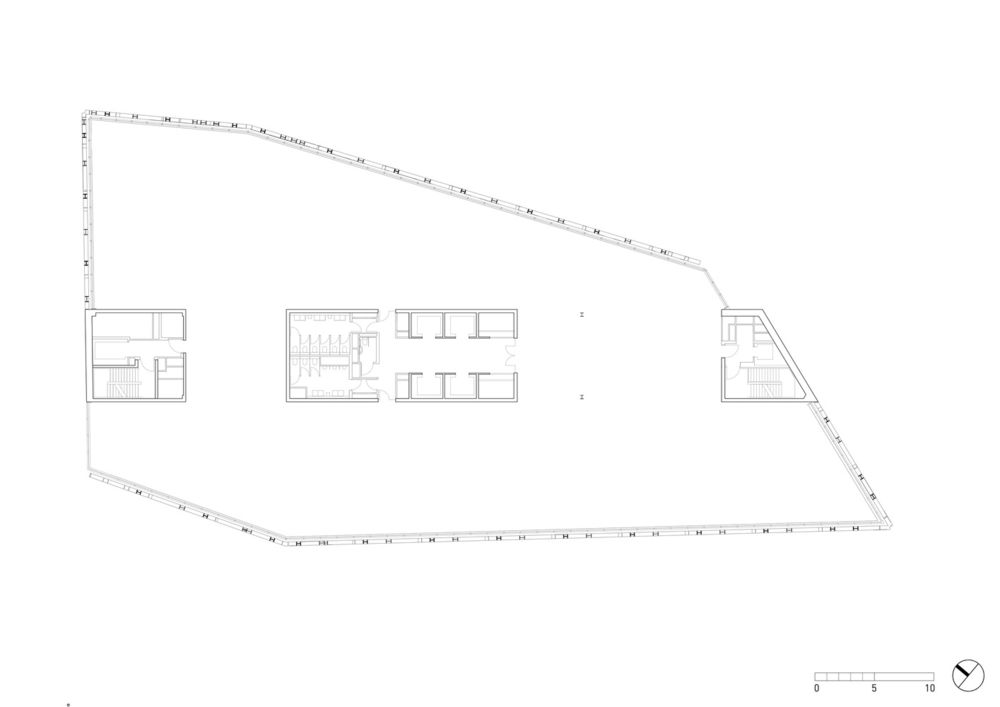

Pushing the superstructure to the outside of the 32,912 sqm building delivers column-free internal floor space – spanning 12-16m to the dispersed central cores and 66m from end to end. Occupiers can have maximum flexibility with their fit-outs and enjoy unimpeded views.

The external structure shades windows, allowing larger areas of glazing and deep daylight penetration. Beams are tapered as they approach the facade, permitting the use of taller perimeter glazing and further increasing daylight. This impression of light and space is further enhanced by the high floor-to-ceiling dimensions. Fletcher Priest and Arup worked with building services engineer Cundall to integrate the floor structure and services into as tight a zone as possible, some 100mm less than normal for workplace buildings, to further increase ceiling heights.

This aesthetic means that materials such as concrete, steel, and sawn oak have been left exposed internally, and service ducts and pipes are visible. Extra emphasis has been put on the quality of construction - a particular challenge in areas such as the core, where huge areas of concrete required a consistent finish and had to remain protected during construction. Extensive full-scale physical mock-ups and integrated digital modelling became key design tools.

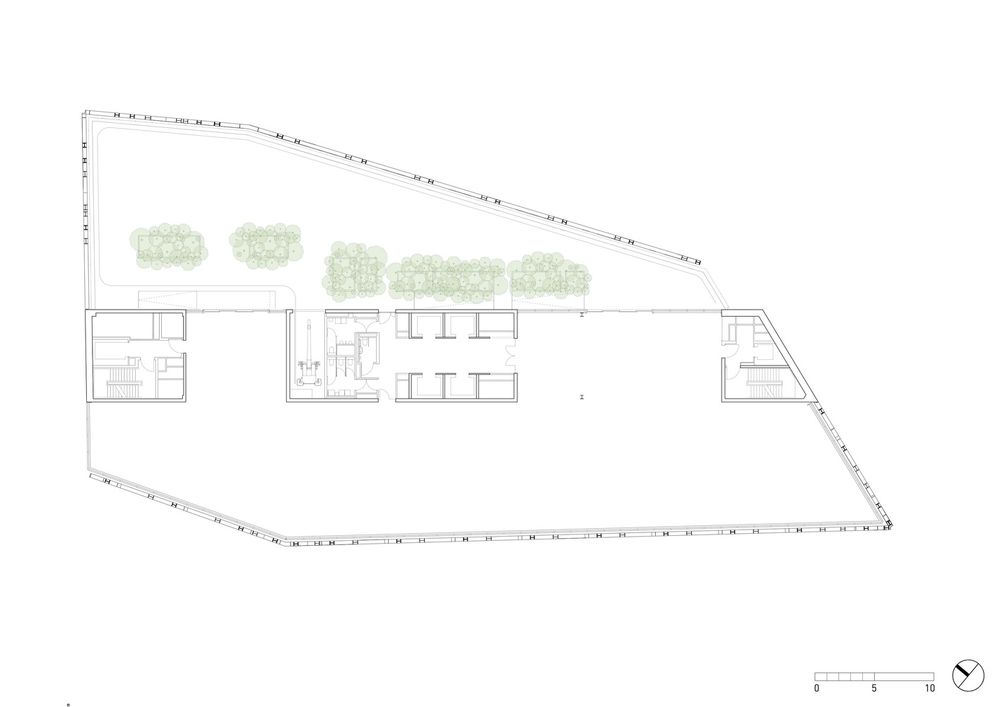

Environment and social sustainability were central to the ambitions of both the design team and the client. The complex external diagrid structure provides 20% shading to the facades, helping to reduce energy demand. An Aquifer Thermal Energy Store (ATES), with two forty-storey deep boreholes, provides low- carbon heating and cooling. Greywater from showers is recycled to flush the building’s bathrooms. Exposed undersides of the structural precast concrete floor panels, made in a state-of-the-art robotic plant, help to deliver comfortable interior thermal gradients and more volume per person. Leaving the ceilings exposed also saved more than 540 tonnes of embodied carbon. More than 90% of construction waste was recycled and ground blast-furnace slag (a waste product from iron and steel production) was used in the concrete.

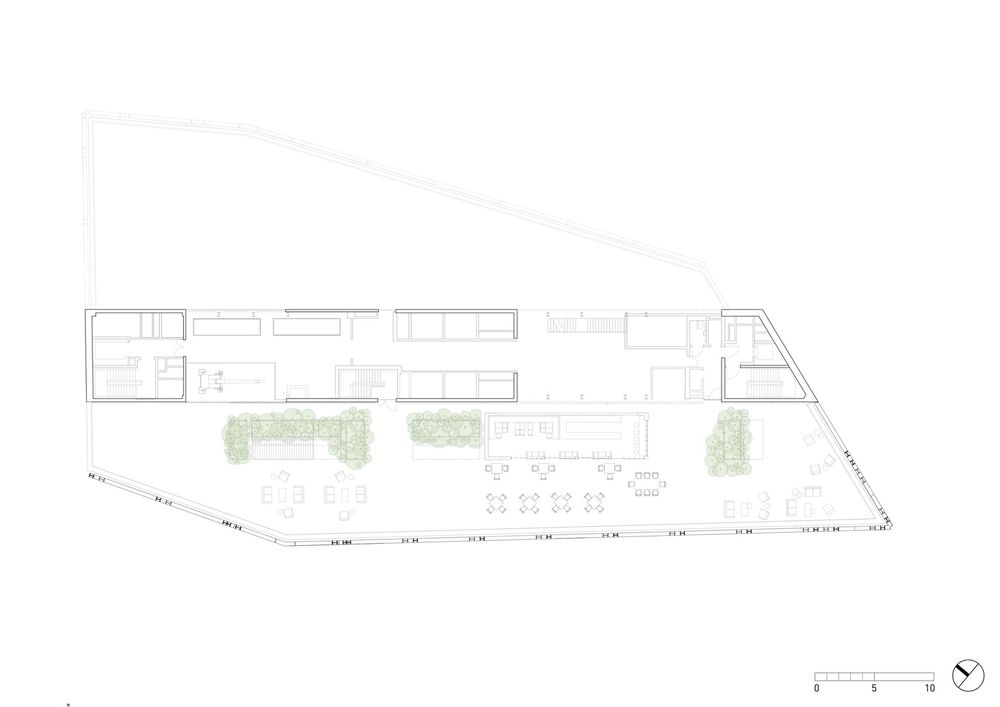

The existing building on the site spanned this section of the canal blocking access and views along the canal. The canal-side walk is now publicly accessible for the first time in more than 200 years and will eventually provide new pedestrian routes to nearby Little Venice, as well as a new public space and artwork. Brunel Building is one of the surprisingly few canal-side developments in London with its main entrance on a canal.

Motorized hangar-sized glazed sliding doors can be rolled back to provide an extension to the new tree-lined towpath walkway. Passers-by can visit the canal-side restaurant café and bar and view the public art in the triple-height reception concourse. Meanwhile, occupiers have access to two expansive roof terraces with views across London. Soft landscaping, planters with wildflowers, trees, and nesting boxes all contribute toward re-establishing the local ecology in what was previously a light-industrial area.

Such a rich and complex building, which took three years to construct, could only be delivered by harnessing the latest digital tools, developing and coordinating the design, and managing the logistics for fabrication and construction. “We could visualise the design via simulated walkthroughs and virtual reality headsets, enabling the architects, designers, and suppliers to check for clashes, such as pipework running through beams, so we could make and assess changes holistically,” says Fletcher Priest associate Chris Radley.

All workspace was oversubscribed long before completion, Brunel is the new home to a remarkably diverse ecology from many sectors; Sony Pictures, the Premier League, Alpha FX, Splunk, Hellman & Friedman, Coach, and Paymentsense.

▼项目更多图片