范杜斯堡的奥贝特咖啡厅 | 几何抽象与空间激活的完美结合

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Claude Truong-Ngoc

维基媒体用户Claude Truong-Ngoc提供

1917年,由画家、雕塑家、装饰艺术家和建筑师组成的协会在荷兰发起了de Stijl运动。反对19世纪主导西方设计的Beaux艺术学派的观赏性和空间教条,该运动的成员反而主张抽象的相对纯洁性。立体派为这场运动提供了重要的灵感,这一运动的特点是大胆的、正交的极简主义。蒙德里安的绘画完全由直角的矩形和直线组成,逐渐放弃了对现实的符号表征,而转向了自己抽象的视觉节奏。这种直线风格有助于将其翻译成三维形式-这一任务将由蒙德里安的同时代人之一、画家兼建筑师西奥·范杜斯堡承担。

The De Stijl movement began in the Netherlands in 1917 by an association of painters, sculptors, decorative artists, and architects. Rejecting the ornamental and spatial dogma of the Beaux-Arts school that had dominated Western design in the 19th century, members of the movement instead advocated for the relative purity of abstraction. Cubism provided a significant inspiration for the movement, which came to be characterized by bold, orthogonal minimalism. The paintings of Mondrian, composed purely of rectangles and straight lines at right angles, gradually abandoned symbolic representations of reality in favor of their own abstract visual rhythm. This rectilinear style lent itself toward translation into three-dimensional form – a task that would be undertaken by one of Mondrian’s contemporaries, a painter and architect named Theo van Doesburg.[1]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Claude Truong-Ngoc

维基媒体用户Claude Truong-Ngoc提供

范杜斯堡1883年生于荷兰乌得勒支,原名克里斯蒂安·埃米尔·玛丽·库珀,是一位自学的艺术家和建筑师。[2]1917年,范杜斯堡开始出版“德斯蒂尔”杂志,在他的职业生涯中,许多影响他的艺术家和设计师做出了贡献。[3]达达主义杂志“Mécano”上,他还以1923年题为“面向建设性的诗歌”(“迈向建设性的诗歌”)的宣言而闻名。在其中,他表达了与超现实主义相一致的信念。[4]他自己的设计作品侧重于利用色彩作为激活空间的手段。他认为,这有助于观众更好地欣赏抽象形式。范杜斯堡经常与其他艺术家合作,拒绝个人艺术的自我中心主义。因此,当他受命为斯特拉斯堡市中心的奥贝特咖啡厅设计几个新的室内装饰时,他与艺术家让·阿普和他的妻子索菲·图伯一起这样做。

Born in Utrecht, Netherlands in 1883, Van Doesburg (originally named Christian Emil Marie Küpper) was a self-educated artist and architect.[2] It was Van Doesburg who would, in 1917, begin publishing the journal entitled De Stijl, featuring contributions from many of the artists and designers who had influenced him during his career.[3] He is additionally known for his 1923 manifesto entitled “Tot een constructieve dichtkunst” (“Toward a constructive poetry”) in the Dadaist journal Mécano, in which he expressed beliefs in line with what would become Surrealism.[4] His own design work was focused on the use of color as a means of activating space. This, he believed, helped viewers to better appreciate abstract form. Van Doesburg often worked in collaboration with other artists, rejecting the egocentrism of individual artistry. It therefore followed that when he was tasked with designing several new interiors for the Café l’Aubette in central Strasbourg, he did so in tandem with artist Jean Arp and his wife, Sophie Täuber.[5]

Exterior of the Aubette as seen from the Place Kléber. ImageCourtesy of Wikimedia user Claude Truong-Ngoc

从Kléber的地方可以看到奥贝特的外表。图片-维基媒体用户克劳德·特鲁翁-恩戈克的礼貌

奥贝特建筑于1767年,由建筑师弗朗索瓦·布朗德尔(Fran Ois Blondel)建造。在法国政府的委托下,布隆德尔建造了一座能反映当时最新风格的建筑,在克莱贝尔广场的整个北缘建造了一座带有直立面的巴洛克式建筑。这座建筑作为军事设施的最初用途是奥贝特(Aubette),因为命令是在奥贝(Aube)发布的。1845年,一家咖啡馆在这座建筑中开张,1867年,奥贝特成为斯特拉斯堡音乐学院的所在地。1911年,市政府召集了46名建筑师,重新设计了奥贝特和克莱贝尔的全部建筑;然而,第一次世界大战的爆发阻止了这个被20世纪20年代放弃的项目。

The Aubette was built in 1767 by the architect François Blondel. Commissioned by the French government to construct a building that would reflect the latest style of the time, Blondel created a Baroque structure with a straight façade along the entire northern edge of the Place Kléber. The building’s original use as a military facility gave it the name Aubette, as orders were issued at aube, or dawn. A café was opened in the building in 1845, and in 1867, the Aubette became home to Strasbourg’s School of Music. In 1911, the city government called together 46 architects to redesign both the Aubette and the entirety of the Place Kléber; however, the outbreak of the First World War forestalled the project, which was abandoned by the 1920s.[6]

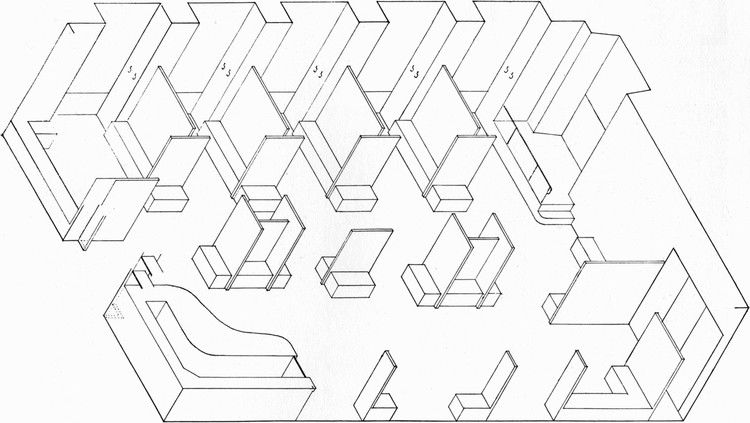

Axonometric diagram of the Café-Brasserie. ImageTheo van Doesburg

咖啡厅轴测图ImageTheo van Doesburg

Van Doesburg’s involvement with the Aubette began in September of 1926. Convinced by his clients to set up an office on the Place Kléber itself, he began drawing up plans that would correspond with the new functions of the space. Included in the required program were a café, tea room, two bars, telephone booths, billiard rooms, two banquet halls with an adjoining foyer, kitchens, various offices, and staff quarters.[7] Although Van Doesburg, Arp, and Täuber ostensibly worked as a team, their actual design process was surprisingly disjointed; rooms were designed by different artists with little in the way of organized collaboration, allowing their personal styles to shape the individual spaces of the building.[8]

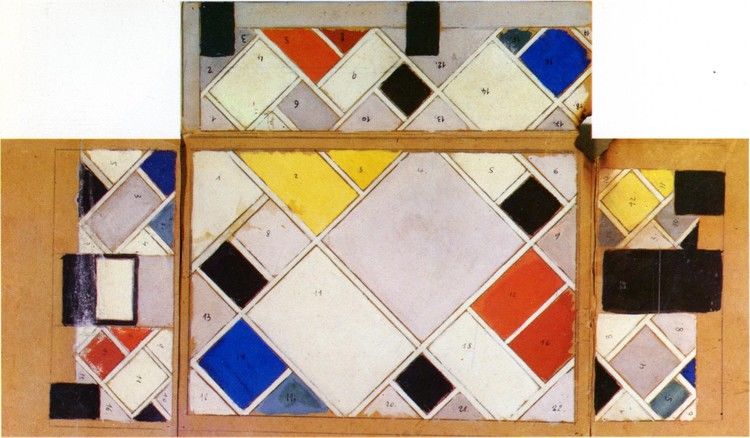

Procedural painting for the Ciné-Dancing Hall. ImageTheo van Doesburg

Ciné-舞厅的程序绘画。ImageTheo van Doesburg

虽然Arps的作品反映了他们以前对达达运动的参与,但范杜斯堡却看到了实施他自己的元素主义理论的机会。[9]与蒙德里安一样,他的设计完全是直线、正交的;墙壁上覆盖着色彩鲜艳的大格子。然而,范杜斯堡并没有严格地约束自己在不适合他的情况下遵守德斯蒂吉尔的原则;为了创造更有表现力、更有活力的空间,他会打破这些原则。

While the Arps’ work reflected their former involvement in the Dada movement, Van Doesburg instead saw the opportunity to implement his own theories of Elementarism.[9] Much like Mondrian, he designed in a purely rectilinear, orthogonal manner; the walls were covered in large grids of brightly colored rectangles. However, Van Doesburg did not rigorously bind himself to the principles of De Stijl when it did not suit him; he would break them in the interest of creating more expressive, dynamic spaces.[10]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Claude Truong-Ngoc

维基媒体用户Claude Truong-Ngoc提供

这种方式也许最好体现在他所谓的“Ciné-舞蹈”大厅-一个设计成电影院和舞厅或歌舞厅的空间。在这里,特征的de Stijl矩形倾斜在一个45度的角度到地面,创造了一种视觉张力与方向的门,窗户,座位隔间,他们包络。[11]范杜斯堡还采用浮雕,以增加强调和兴趣的墙壁和天花板;在颜色不能令人满意地激活表面的情况下,矩形板的轻微挤压将起到补偿作用。[12]范杜斯堡可能在编撰德斯蒂吉尔的原则方面发挥了很大作用,但是在他的设计的各个方面-从选择完成材料到为路标创建新字体-他的工作都是为了响应奥贝特的特殊环境,就像他在他帮助创建的指南中所做的那样。

This approach is perhaps best reflected in what he called the “Ciné-Dancing” hall – a space designed to function as both a film theater and a ballroom or cabaret. Here, the characteristic De Stijl rectangles are tilted at a 45-degree angle to the ground, creating a visual tension with the orientation of the doors, windows, and seating cubicles they envelop.[11] Van Doesburg also employed relief to add emphasis and interest to the walls and ceilings; where color would not satisfactorily activate a surface, the slight extrusion of the rectangular panel would compensate.[12] Van Doesburg may have played a large part in codifying the tenets of De Stijl, but in all aspects of his design—from choosing finish materials to creating a new typeface for signage—he worked as much in response to the particular environment of the Aubette as he did within the very guidelines he had helped to create.[13]

Courtesy of Wikimedia user Claude Truong-Ngoc

维基媒体用户Claude Truong-Ngoc提供

欧贝特咖啡馆(Cafél‘Aubette)的激进内饰,虽然现在被誉为德·斯蒂尔(De Stijl)建筑的杰作,但并未受到咖啡厅主顾的大力赞扬。[14]在不到10年的时间里,室内风格再次发生了变化;直到20世纪60年代,才考虑恢复范德斯堡(Van Doesburg)的设计。1985年至1994年期间,根据时期照片和建筑图纸修复了CINé舞厅;其余的内部建筑随后又恢复,重点是尽可能保存原始材料。为了精确复制范杜斯堡和阿尔普斯所选择的颜色,人们采取了细致的措施,到了2006年,奥贝特又恢复到了20世纪20年代的样子。[15]如今,这座咖啡馆被指定为一个具有历史意义的地标,这座咖啡馆仍然是平面设计与建筑结合的纪念碑,德斯蒂吉尔大胆的几何学原则为两者的结合提供了便利。

The radical interiors of the Café l’Aubette, while now lauded as a masterpiece of De Stijl architecture, were not met with great acclaim by the café’s patrons.[14] After less than a decade, the interior style was altered once again; it was not until the 1960s that restoration of Van Doesburg’s design was even considered. The ciné-dancing hall was restored between 1985 and 1994 based on period photographs and architectural drawings; the rest of the interior followed later, with the emphasis being on conservation of the original materials wherever possible. Meticulous care was taken to reproduce exactly the colors chosen by Van Doesburg and the Arps, and by 2006, the Aubette was restored to its 1920s appearance.[15] Now designated a historic landmark, the Café l’Aubette remains a monument to the marriage of graphic design and architecture facilitated by De Stijl’s principles of bold geometry.

参考文献[1]柯蒂斯,威廉J.R.现代建筑,自1900年。伦敦:Phaidon,1996年。第151-153页。[2]Poulin,Richard。平面设计建筑-20世纪的历史:现代世界中的类型、形象、符号和视觉故事指南。贝弗利:洛克波特出版社,2012年。P79.[3]Raizman,David Seth。现代设计史。上萨德尔河,新泽西州:普伦提斯霍尔,2004年。P 184-187。[4]“MéCano”。达达和现代主义杂志。2016年7月16日。[进入]。[5]Raizman,p 184-187。[6]Jaffé,Hans Ludwig C.de Stijl。纽约:H.N.Abrams出版社,1971年。p 232。[7]Jaffé,p 233-324。[8]Raizman,p 187。[9]Raizman,p 187。[10]Poulin,P79。[11]Raizman,p 187。[12]Poulin,P79。[13]Jaffé,第235-237页。[14]Poulin,P79。[15]“恢复”。斯特拉斯堡La Ville Musées de La Ville de斯特拉斯堡。2016年7月6日查阅。[进入]。

References [1] Curtis, William J. R. Modern Architecture since 1900. London: Phaidon, 1996. p151-153. [2] Poulin, Richard. Graphic Design Architecture a 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in the Modern World. Beverly: Rockport Publishers, 2012. p79. [3] Raizman, David Seth. History of Modern Design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004. P184-187. [4] "Mécano." DADA and Modernist Magazines. Accessed July 16, 2016. [access]. [5] Raizman, p184-187. [6] Jaffé, Hans Ludwig C. De Stijl. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1971. p232. [7] Jaffé, p233-324. [8] Raizman, p187. [9] Raizman, p187. [10] Poulin, p79. [11] Raizman, p187. [12] Poulin, p79. [13] Jaffé, p235-237. [14] Poulin, p79. [15] "Restoration." Musées De La Ville De Strasbourg. Accessed July 06, 2016. [access].

建筑师Theo van Doesburg地点31 Place Kléber,法国斯特拉斯堡67000级室内设计师,主管西奥·范杜斯堡设计团队,索菲·蒂伯项目,1926年

Architects Theo van Doesburg Location 31 Place Kléber, 67000 Strasbourg, France Category Interiors Architecture Architect in Charge Theo van Doesburg Design Team Sophie Täuber Project Year 1926